Epidemics That Didn't Happen

Case Study:

Cholera in Burkina Faso

About Cholera

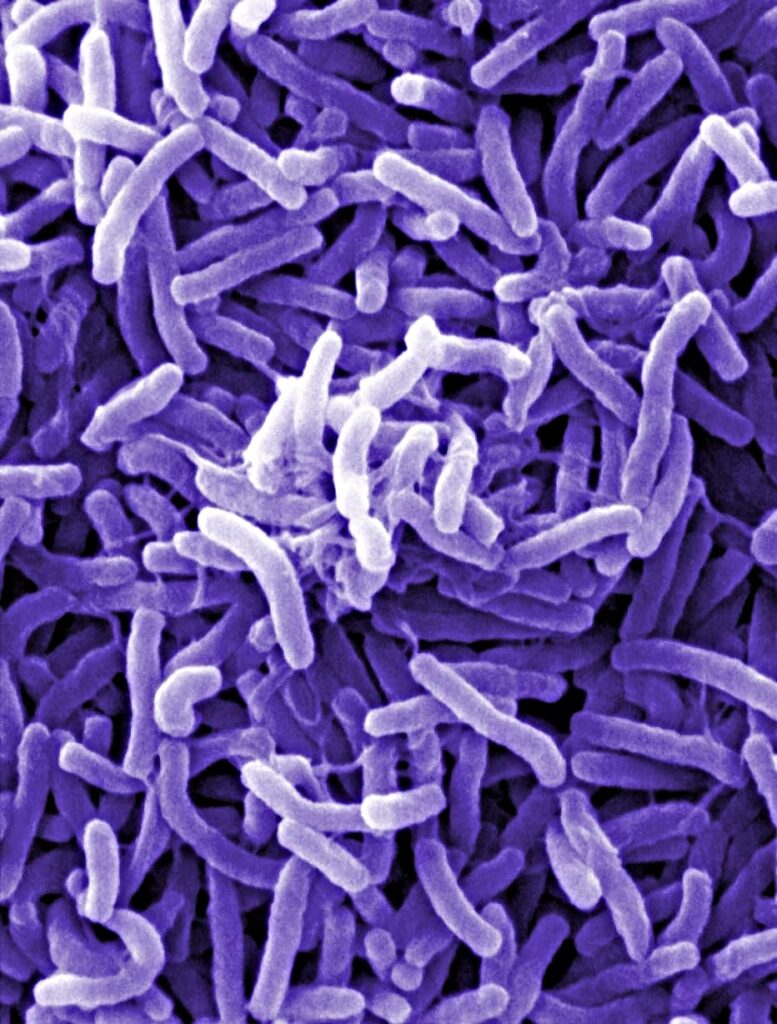

Cholera is a highly infectious diarrheal disease caused by bacteria in contaminated food or water. Every year, the world sees an estimated 3 million cases and 100,000 deaths from the disease.1

Cholera was first described in a Sanskrit text dated to the 5th century BCE. Over the centuries, the disease has caused seven pandemics, the first of which began in 1817 in the Ganges delta region of India.

In 1854, a London outbreak was traced back to a single water pump, a discovery which ultimately led to improved water and sanitation systems that have effectively eliminated outbreaks in high-income countries. However, nearly 1 billion people worldwide still drink untreated water taken directly from unprotected sources, and over 2 billion people have no way to safely dispose of human waste, particularly in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.2 In areas with inadequate sanitation and access to clean water, cholera can spread like wildfire. Recent outbreaks in Yemen and Haiti have caused nearly 2 million cases and more than 12,000 deaths.3

For most of those infected, the disease is mild and resolves on its own. However, approximately 10% of patients will experience severe symptoms, including intense watery diarrhea, dehydration, leg cramps and vomiting.4 Cholera can be successfully treated with intravenous fluids and antibiotics, but left untreated, the disease can kill within hours.5 Although supplies of cholera vaccines have increased in recent years, they are only 65% effective and, alone, cannot prevent or suppress outbreaks. 6

In areas with inadequate sanitation and access to clean water, cholera can spread like wildfire.

WHAT HAPPENED

On the morning of August 15, 2021, a truck driver arrived at a health center in Tanwalbougou, a village about 30 miles from Fada N’gourma, a city in eastern Burkina Faso. He fell unconscious due to severe dehydration after an extreme bout of watery diarrhea and vomiting. The case immediately set off alarms for health officials as the driver had arrived from Niamey, Niger,7 where a cholera outbreak had claimed more than 30 lives already.8 The driver had spent three days in Kantchari, a city in Burkina Faso near the border with Niger, where a fellow driver he was traveling with was treated for vomiting and fever.

On August 17, testing confirmed: it was cholera.9

Eastern Burkina Faso is a regional hub of trade and migration, with populations constantly moving through border crossings. In addition to Niger, the region also borders Mali, Togo and Benin—all of which were dealing with cholera outbreaks at the time.10 Health officials, who hadn’t seen a case of cholera in eastern Burkina Faso since 2011, realized that a single case represented a grave epidemic threat, given how quickly the disease can spread and become rooted in the population. Leaders noted that without decisive action, the country’s health system—already experiencing disruptions due to insecurity—could face a dangerous influx of patients. High population density caused by mass displacement, limited access to safe drinking water and to sanitary latrines all contributed to the country’s vulnerability.11

THE RESPONSE

After the patient arrived at the health center, local health authorities in the Fada health district immediately issued a notification to the government, which allowed national authorities to spring into action that same day and support a coordinated response.12

The initial patient and the four individuals he had been in contact with—fellow drivers and the owner of the vehicle he was taken to the hospital in—were all quickly isolated and monitored.13 Teams were sent to Kantchari to locate the fellow driver who had previously fallen ill to determine if the illness was cholera, identify additional contacts and sanitize areas of concern, including latrines at the border. Contacts and health workers in contact with patients were given prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection. At the same time, regional health authorities, with the support of Burkina Faso’s health cluster coordinated by the World Health Organization,14 updated response plans for cholera that took the country’s security context into account.

The government began briefing the media and stepping up risk communications in the community via radio and in community meetings with local leaders to discuss strategies for preventing further spread of the disease. Health workers visited restaurants and butchers to advise on appropriate hygiene, while distributing supplies for disinfection, protective equipment and medicines. Officials built latrines for outbreak treatment centers to reduce the risk of cholera spreading into communities; they also planned to build new and and conducted trainings in schools on appropriate sanitation.15 Health officials as well as community groups were briefed on the handling of and preventive measures for cholera.

The steps taken by health officials were accelerated by the plans that had been put in place before the outbreak: spurred by cholera outbreaks in surrounding countries, Burkina Faso had developed a national cholera preparedness and response plan, which was finalized in June 2021 and set the stage for a successful response. During a 2020 push to prepare for a cholera outbreak, health leaders had disseminated materials and trained staff to monitor and report on any potential outbreak of cholera. Medicines, protective equipment and disinfectant materials were distributed in the region for officials to use as soon as a case was identified. Communication activities had already begun, along with meetings of regional outbreak management committees.16

In the midst of managing the initial outbreak, officials learned that a second truck driver arriving from Niger fell ill on August 26 and was confirmed to have cholera on August 29. Due to previous preparations and a prompt response by local authorities in Diapaga health district who were already involved in the response to August 15 case, the patient was isolated and treated and the disease spread no further. Following successful treatment, the first truck driver to fall ill was released on August 22 and the second on August 31.17 Two additional suspect cases were identified by enhanced surveillance activities, including one identified at the Kantchari border crossing, who tested negative.18 The rapid detection, case management, contact identification and isolation, as well as strengthening surveillance at points of entry with Niger, prevented new imported cases and helped to contain the outbreak locally in Burkina Faso. The health cluster also organized several meetings, including with other sectors such as water, sanitation and hygiene as well as environmental offices, to help mobilize financial and material resources for the response.

In 2021, West Africa saw nearly 109,000 cases of cholera and over 3,700 deaths. Every country impacted by cholera has seen a case-fatality rate above 1%, the agreed international target,19 except for Burkina Faso, whose case-fatality rate was 0%.

KEY PREPAREDNESS FACTORS

- Risk Assessment & Planning

- Emergency Response Operations

- National Laboratory System

- Disease Surveillance

- National Legislation Policy & Financing

- Human Resources

- Risk Communications

Dr Sonia Marie Ouedraogo, National Professional Officer/Country Readiness, World Health OrganizationThe rapid detection, case management, contact identification and isolation, as well as strengthening surveillance at points of entry with Niger, prevented new imported cases and helped to contain the outbreak locally in Burkina Faso.

Dr Sonia Marie Ouedraogo, National Professional Officer/Country Readiness, World Health OrganizationThe rapid detection, case management, contact identification and isolation, as well as strengthening surveillance at points of entry with Niger, prevented new imported cases and helped to contain the outbreak locally in Burkina Faso.

References

- Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez, AL, et al. (2015). Updated Global Burden of Cholera in Endemic Countries. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(6), e0003832. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832

- Wierzba TF. (2019). Oral Cholera Vaccines and Their Impact on the Global Burden of Disease. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(6), 1294–1301. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1504155

- Wierzba TF. (2019). Oral Cholera Vaccines and Their Impact on the Global Burden of Disease. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(6), 1294–1301. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1504155

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, October 2). Cholera — Illness and Symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/illness.html

- World Health Organization (2022, March 30). Cholera. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera

- Wierzba TF. (2019). Oral Cholera Vaccines and Their Impact on the Global Burden of Disease. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(6), 1294–1301. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1504155

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2021). Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies. Week 34: 16-22 August 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/344445/OEW34-1622082021.pdf

- Relief Web. (2021, August). Niger: Cholera Outbreak – Aug 2021. https://reliefweb.int/disaster/ep-2021-000130-ner

- Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, Eastern Regional Health Directorate. (2021, August). Preparedness and Response Plan: The Cholera Epidemic at the Eastern Regional Level, 2021.

- Sodjinou V, Talisuna A, Braka F, et al. (2022). The 2021 Cholera Outbreak in West Africa: Epidemiology and Public Health Implications. Fortune Journals. https://www.fortunejournals.com/articles/the-2021-cholera-outbreak-in-west-africa-epidemiology-and-public-health-implications.html

- Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, Eastern Regional Health Directorate. (2021, August). Preparedness and Response Plan: The Cholera Epidemic at the Eastern Regional Level, 2021.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2021). Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies. Week 34: 16-22 August 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/344445/OEW34-1622082021.pdf

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2021). Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies. Week 34: 16-22 August 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/344445/OEW34-1622082021.pdf

- The World Health Organization, with hundreds of partners, supports 31 Health Clusters across the world to alleviate the impact of humanitarian emergencies. There is one in Burkina Faso focused on improving health care access and outbreak response. Learn more: https://healthcluster.who.int/countries-and-regions/burkina-faso

- Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, Eastern Regional Health Directorate. (2021, August). Preparedness and Response Plan: The Cholera Epidemic at the Eastern Regional Level, 2021.

- Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, Eastern Regional Health Directorate. (2021, August). Preparedness and Response Plan: The Cholera Epidemic at the Eastern Regional Level, 2021.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2021). Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies. Week 36: 30 August – 5 September 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/345001/OEW36-300805092021.pdf

- Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, Eastern Regional Health Directorate. (2021, September. Ninth Situation Report on the Cholera Epidemic in the Eastern Region, Period of September 12-13.

- World Health Organization (2022, March 30). Cholera. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera