Epidemics That Didn't Happen

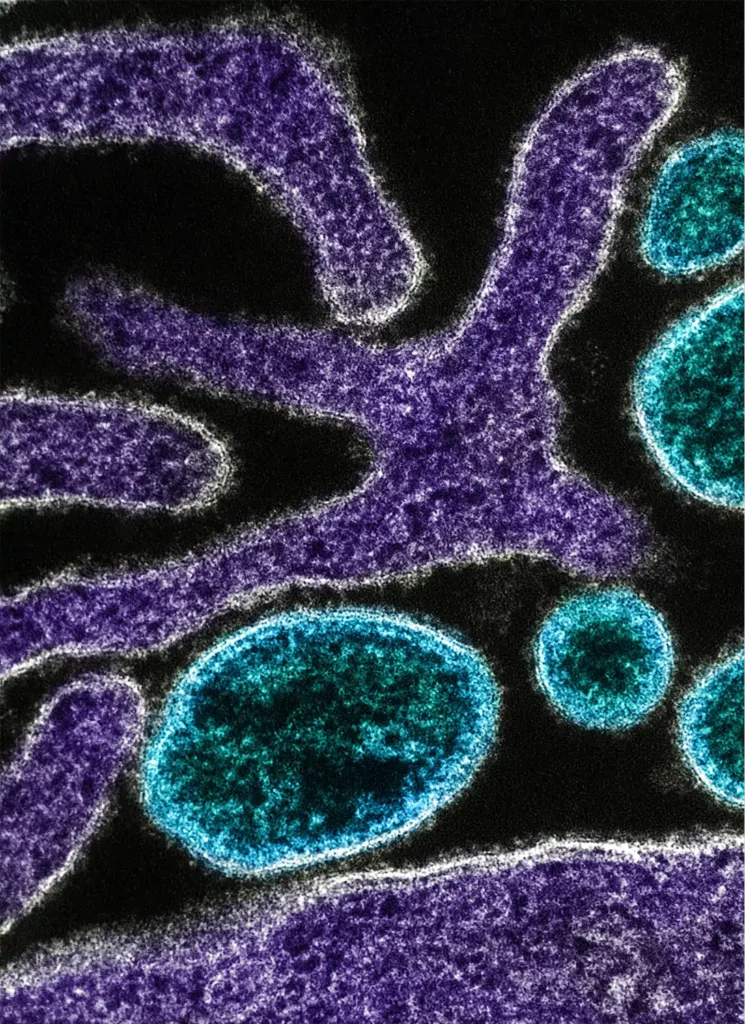

About Nipah

An emerging zoonotic disease of international public health importance, Nipah virus disease causes symptoms ranging from fever, headache and vomiting to acute encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), altered consciousness and seizures. Among survivors, some 20% are left with residual neurological conditions, including seizure disorders.1 The virus was first identified in Malaysia as recently as 1998; the deadly outbreak resulted in 265 cases and 108 deaths.2

With a shocking case-fatality rate of up to 75%, Nipah is a priority for accelerated research and development. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it could well cause a future epidemic in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific region.3 The virus can also cause severe disease in farm animals, leading to important economic impacts. No vaccine or licensed treatment is currently available.

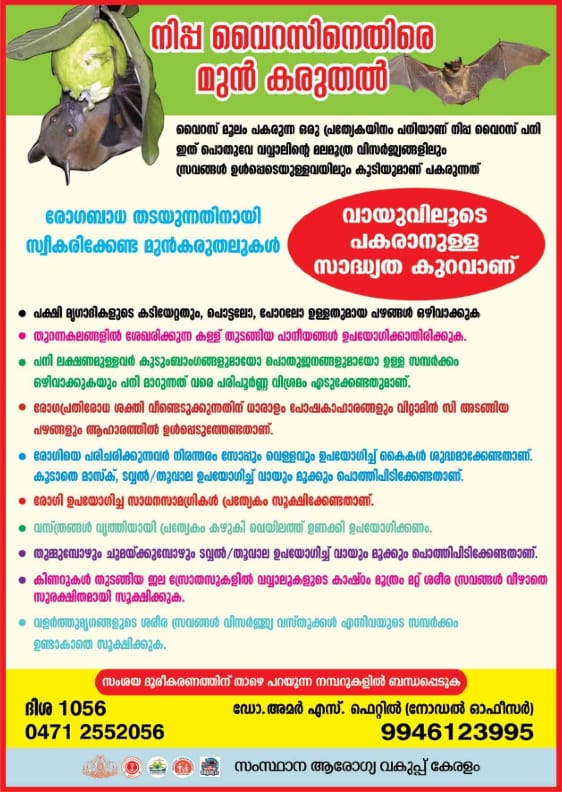

While the first outbreaks of Nipah emerged on pig farms in Malaysia and Singapore, subsequent research has traced the primary vector of the virus to Pteropus fruit bats native to the region, with transmission between animal species occurring as fruit bats drop their infected food waste, urine and feces anywhere they happen to perch.4 Transmission to humans can occur from direct contact with infected animals—including domesticated species, such as dogs and cats—consuming contaminated food (especially raw date palm juice), or close contact with an infected person.

Outbreaks in Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh and India have typically followed a seasonal pattern, emerging during fruit harvesting or Pteropus breeding seasons in winter and spring. And the outbreaks have been lethal. Across the 11 outbreaks in Bangladesh alone since Nipah was detected, 196 cases were confirmed, and 150 of those cases resulted in death.5

With a shocking case-fatality rate of up to 75%, Nipah is a priority for accelerated research and development.

WHAT HAPPENED

On August 29, 2021, the family of a 12-year-old boy who lived near a farm frequented by Pteropus fruit bats brought him to a local clinic in the Kozhikode district of Kerala State with a headache and low-grade fever. Over the next three days, the boy was transferred to one hospital and then another as his condition rapidly deteriorated; he developed serious symptoms including disorientation and loss of consciousness.6

With four previous outbreaks of Nipah virus disease reported in India since its emergence—one of which took place in the very same district of Kozhikode, Kerala7—district doctors were prepared. Although the boy was much younger than previous cases of Nipah and fell sick outside the typical season for infection, his tell-tale presentation with encephalitis and the clear reporting protocols for symptoms meant that samples were immediately sent to the National Institute of Virology in Pune for testing on September 3. The sample was confirmed to contain Nipah antibodies the following day. Tragically, the boy succumbed to the virus on September 5.

Thanks to Kerala State’s efforts to step up its preparedness and a robust response, the 2021 outbreak began and ended with a single case.

Dr. Chandni RHealth care workers were geared to work 24/7. From the health minister to the cleaning staff, we were all working together as one team. The only thing that mattered was to curtail this outbreak as quickly as possible.

Head of Emergency Medicine at Kozhikode Government Medical College Hospital, Professor of Medicine and

Nodal Officer for Nipah outbreaks in Kerala in 2018 and 2021

Dr. Chandni RHealth care workers were geared to work 24/7. From the health minister to the cleaning staff, we were all working together as one team. The only thing that mattered was to curtail this outbreak as quickly as possible.

Head of Emergency Medicine at Kozhikode Government Medical College Hospital, Professor of Medicine and

Nodal Officer for Nipah outbreaks in Kerala in 2018 and 2021

THE RESPONSE

As soon as Nipah was confirmed on September 4, health authorities were alerted and senior health officials across local, district, state and national bodies convened in the Kozhikode district to plan and implement response measures, releasing a detailed action plan and practice manual for all stakeholders on September 5.8 The group would meet every day—twice a day, at first—establishing a 24-hour Emergency Operations Center in a local guesthouse where they worked together around the clock.

With the help of a multi-disciplinary team from the Indian Government’s National Centre for Disease Control, rapid and exhaustive epidemiological investigations quickly identified 240 of the index case’s contacts and other potential cases in nearby districts; officials also conducted extensive sampling and testing of the fruit bats near his home—all within two days of laboratory confirmation.9 The district had learned from previous outbreaks how important contact tracing and case investigation would be to containment efforts, as well as establishing triage centers and isolation facilities to control transmission, a field laboratory for faster test results, and risk communication activities targeting health literacy and behavior change.

The public was informed about Nipah virus transmission and prevention measures through daily press briefings and a “No Nipah” media campaign, and neighboring states were quickly alerted to the potential threat. After a conservative waiting period of 42 days with no new cases detected (twice the length of the potential incubation period of 21 days), India’s Health Minister announced the end of the outbreak on October 17, 2021.10

Kerala State’s swift response was informed by past experience with Nipah—and a readiness to address weaknesses that earlier outbreaks had exposed. Back in May of 2018, 18 cases of Nipah were confirmed, 17 of which proved fatal—including a health care worker.11 Despite never having faced an outbreak of this emerging disease before, health authorities did eventually contain it by leveraging the strength of Kerala’s health system.12 Still, the response to 2018’s outbreak required a great deal of improvisation to mount, and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) along with government authorities and international partners made it their mission to step up preparedness for Nipah and other potential epidemic threats, channeling their experience into system-wide improvement.

They asked WHO to conduct an external review of their response efforts to understand where they could improve. WHO’s review identified gaps in areas such as surveillance capacity, data sharing, timely data collection and support for health care workers, including training and improved infection prevention and control practices.13 Officials subsequently undertook efforts to fill these gaps in preparation for further infectious disease outbreaks.

And just in the nick of time. The preparedness efforts initiated by Kerala State in response to the Nipah outbreaks of 2018 and 2019—including stockpiling personal protective equipment, improving multisectoral coordination and accountability mechanisms, developing a comprehensive “playbook” for future outbreaks and implementing “mock drills” to test capacity—would prove indispensable when COVID-19 struck the region in January of 2020. The system was prepared, it was just “a question of customizing for our needs at the time,” said Dr. Chandni.

Kerala State was able to maintain the integrity of its health system and keep case counts low, while so many others were caught unprepared. And when the Nipah virus re-emerged in Kozhikode in 2021, another potentially catastrophic outbreak was contained to a single case.14,15

KEY PREPAREDNESS FACTORS

- Risk Assessment & Planning

- Emergency Response Operations

- National Laboratory System

- Disease Surveillance

- National Legislation Policy & Financing

- Human Resources

- Risk Communications

K K Shailaja, Minister for Health & Family Welfare Social Justice, Woman and Child Development as quoted in Management Plan for Nipah Outbreak in Kozhikode—5th Sept 2021During the first outbreak, there was limited knowledge available, especially related to actions at the grassroots level. But the health system responded very well, contained the outbreak and gained experience. At the time of second outbreak, again the health department, along with the district administration, launched coordinated actions and contained the epidemic.

K K Shailaja, Minister for Health & Family Welfare Social Justice, Woman and Child Development as quoted in Management Plan for Nipah Outbreak in Kozhikode—5th Sept 2021During the first outbreak, there was limited knowledge available, especially related to actions at the grassroots level. But the health system responded very well, contained the outbreak and gained experience. At the time of second outbreak, again the health department, along with the district administration, launched coordinated actions and contained the epidemic.

References

- World Health Organization. (2018, May 30). Nipah Virus. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nipah-virus

- Looi, LM, Chua, KB. (2007). Lessons from the Nipah Virus Outbreak in Malaysia. The Malaysian Journal of Pathology, 29(2), 63–67. http://www.mjpath.org.my/2007.2/02Nipah_Virus_lessons.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2018, May 30). Nipah Virus. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nipah-virus

- Looi, LM, Chua, KB. (2007). Lessons from the Nipah Virus Outbreak in Malaysia. The Malaysian Journal of Pathology, 29(2), 63–67. http://www.mjpath.org.my/2007.2/02Nipah_Virus_lessons.pdf

- Rahman M, Chakraborty A. (2012). Nipah Virus Outbreaks in Bangladesh: A Deadly Infectious Disease. World Health Organization South-East Asia Journal of Public Health. 1(2), 2018-212. https://www.who-seajph.org/article.asp?issn=2224-3151;year=2012;volume=1;issue=2;spage=208;epage=212;aulast=Rahman;type=3#:~:text=A%20total%20of%20196%20cases,factors%20for%20acquiring%20the%20disease

- Thakur V, Thakur P, Ratho RK. (2022). Nipah Outbreak: Is it the Beginning of Another Pandemic in the Era of COVID-19 and Zika? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 99, 25–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.09.015

- Thakur V, Thakur P, Ratho RK. (2022). Nipah Outbreak: Is it the Beginning of Another Pandemic in the Era of COVID-19 and Zika? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 99, 25–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.09.015

- World Health Organization. (2021, September 24). Nipah Virus Disease – India. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/nipah-virus-disease—india

- Yadav PD, Sahay RR, Balakrishnan A. (2022). Nipah Virus Outbreak in Kerala State, India Amidst of COVID-19 Pandemic. Fronters in Public Health, Infectious Diseases – Surveillance, Prevention and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.818545

- News Desk. (2021, October 17). Kerala Health Minister: Kozhikode District Can Now Said to be Free of Nipah Virus. Outbreak News Today. http://outbreaknewstoday.com/kerala-health-minister-kozhikode-district-can-now-said-to-be-free-of-nipah-virus-65319/

- BBC News Desk. (2018, May 22). Lini Puthussery: India’s ‘Hero’ Nurse who Died Battling Nipah Virus. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-44207740

- World Health Organization. (2021, September 24). Nipah Virus Disease – India. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/nipah-virus-disease—india

- World Health Organization. (2018). Nipah Virus Outbreak in Kerala. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/outbreaks-and-emergencies/health-emergency-information-risk-assessment/surveillance-and-risk-assessment/nipah-virus-outbreak-in-kerala

- Thomas L. (2021, December 15). Containing a Nipah Virus Outbreak Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20211215/Containing-a-Nipah-virus-outbreak-amidst-the-COVID-19-pandemic.aspx

- Thakur V, Thakur P, Ratho RK. (2022). Nipah Outbreak: Is it the Beginning of Another Pandemic in the Era of COVID-19 and Zika? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 99, 25–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.09.015