Epidemics that didn't happen

Lassa Fever in Ghana

Government health authorities made skillful use of emergency funds to rapidly contain an outbreak.

About Lassa

Lassa fever is a zoonotic viral illness endemic in some West African countries. The virus is carried by the common African rat, which can infect humans that touch items contaminated by its urine or feces.1 Humans who handle raw rat meat, which may be sold for food, are at particular risk of infection. About 100,000 to 300,000 people are infected each year, and about 5,000 die.2 Infected people can pass the virus to others through contact with blood and other body fluids. This makes health care workers particularly vulnerable, which can add pressure to health systems, especially in areas with limited resources.

Virus Image: Scanning electron micrograph of Lassa virus budding off a cell. Credit: NIAID

Header: Head porter selling fish at Agbogbloshie Market in Accra, Ghana. Credit: Jonathan Torgovnik via Getty Images

As many as 15% of hospitalized patients die during epidemics—preventing and quickly containing Lassa fever outbreaks is essential.

Rat chewing a hole in a garbage bag. Credit: Jacques Julien via Getty Images

Eighty percent of those infected have mild or no symptoms, but one in five become severely ill. Most symptoms of Lassa fever are mild or not unique to the illness, such as a low fever, fatigue, weakness, and headache.3 But severely ill individuals can display more specific symptoms including bleeding from the gums, nose, or stomach, difficulty breathing, swelling in the face, vomiting, pain in the mid-section of the body, and going into shock. As many as 15% of hospitalized patients die during epidemics,2 which makes preventing and quickly containing Lassa fever outbreaks essential.

In recent years, outbreaks and related fatalities have increased substantially in some West African countries. Given its epidemic potential, Lassa virus is a significant and growing health security concern for the region.5

Man coughing. Credit: Wazzkii/Shutterstock

What Happened

On February 17, 2023, a 40-year-old trader at Agbogbloshie Market arrived at Accra’s Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital with severe symptoms including difficulty breathing, widespread rashes and bloody diarrhea indicating internal bleeding. She had been sick for two weeks before seeking medical attention and died within 5 hours of arriving at the hospital. Given the severity of the patient’s symptoms, clinicians at the hospital suspected Lassa fever and sent samples for laboratory testing. On February 24, test results confirmed that both the patient—and the 33-year-old medical officer who cared for her—tested positive for Lassa fever. The hospital notified the Ghana Health Service (GHS) to initiate a comprehensive response effort.

Agbogbloshie Market in Accra, Ghana. Credit: Thomas Imo via Getty Images

Agbogbloshie Market in Accra, Ghana. Credit: Thomas Imo via Getty Images

The Response

As soon as Korle-Bu hospital sounded the alarm, GHS activated public health emergency management committees at the national, regional and local levels. Committees in Accra were tasked with coordinating local response activities under the direction of a National Public Health Emergency Operations Centre, which provided guidance on specific actions committees should take to find, treat and prevent cases. The committees traced and tested people who’d had contact with the two confirmed cases and instructed them to self-quarantine while awaiting results. District-level teams in Accra ultimately identified 237 people who had interacted with either the woman who died or the medical officer who treated her, including many health care workers in addition to family members and close friends. Anyone who tested positive was referred to the Ghana Infectious Disease Centre to manage and treat their symptoms.

As little as $5,000 in emergency funding can save lives and hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs.

Recording radio messages as part of a community engagement campaign. Courtesy of Gifty Ofori Ansah

According to GHS, past Lassa responses had been limited by lack of emergency funds, which delayed their efforts and allowed misinformation and rumors to flourish. This time, rapid outbreak financing allowed the team to complete critical response activities it simply wouldn’t have the means to complete. Rapid outbreak financing typically allows organizations to use funds flexibly according to their needs. Pilot studies have shown that rapid outbreak financing can fundamentally alter the trajectory of an outbreak, and as little as $5,000 in emergency funding can save lives and hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs.6

By February 26, an additional 25 cases of Lassa fever had been confirmed. GHS requested funding to support its investigation and response efforts, which included accommodation, transportation, production of communication materials, personal protective equipment and essential medications. On February 28, they received $20,000 in grant funding from Resolve to Save Lives. Together with health leaders from across Accra, GHS held a remote learning session to teach 150 health promotion officers how to recognize, prevent, and stop the spread of Lassa fever and how to encourage necessary behavior changes in their communities. These officers in turn helped train another 500+ hospital staff, community health workers and volunteers. The rapid outbreak financing allowed these clinical staff and volunteers to travel throughout Accra and share the message using meetings, posters and leaflets. The team also created radio jingles, text messages and social media posts to reach an even wider audience.

Meeting between the response team and local community stakeholders. Courtesy of Gifty Ofori Ansah

Outdoor community awareness session. Courtesy of Gifty Ofori Ansah

The bustling Agbogbloshie Market—where the woman who died sold produce—is one of the largest open-air markets in Ghana. The response team identified the market as the likely source of her infection, so health promotion officers visited this market, as well as others across Accra, and educated 1,200 vendors how to spot and prevent Lassa fever. Vendors were also encouraged to wash their hands frequently and taught how to safely handle high-risk items like bushmeat. Teams also provided information to more than 7,800 individuals participating in religious services and more than 5,000 students at 200 schools. Jingles and educational programming in multiple local languages, meanwhile, helped reach an additional 2 million people via radio and television.

While nearby countries such as Nigeria are seeing a surge in both Lassa fever cases and case fatality rates—which rocketed to more than 20% in 2023s45—the response in Ghana illustrates how early, flexible funding can enable a rapid, coordinated response and produce much better outcomes for affected communities. GHS intends to build on this success by partnering with Ghana Wildlife Division to depopulate rats in marketplaces and by working with government authorities to conduct a comprehensive environmental assessment of high-risk areas, both in service of minimizing the potential for future outbreaks.

Ultimately, the rapid and comprehensive response initiated by GHS contained this outbreak to 27 cases, one fatal, across 5 districts in Accra. By March 27, a total of 237 traced contacts had completed 21 days of follow-up and, with no additional cases found, the outbreak was officially declared over on May 2.

Enablers

Availability of early response funding

Risk communication and community engagement

Timeline

Emergence

Detection

Notification & Response

Control

The response in Ghana illustrates how a coordinated response, backed with flexible, early funding, can produce much better outcomes for affected communities.

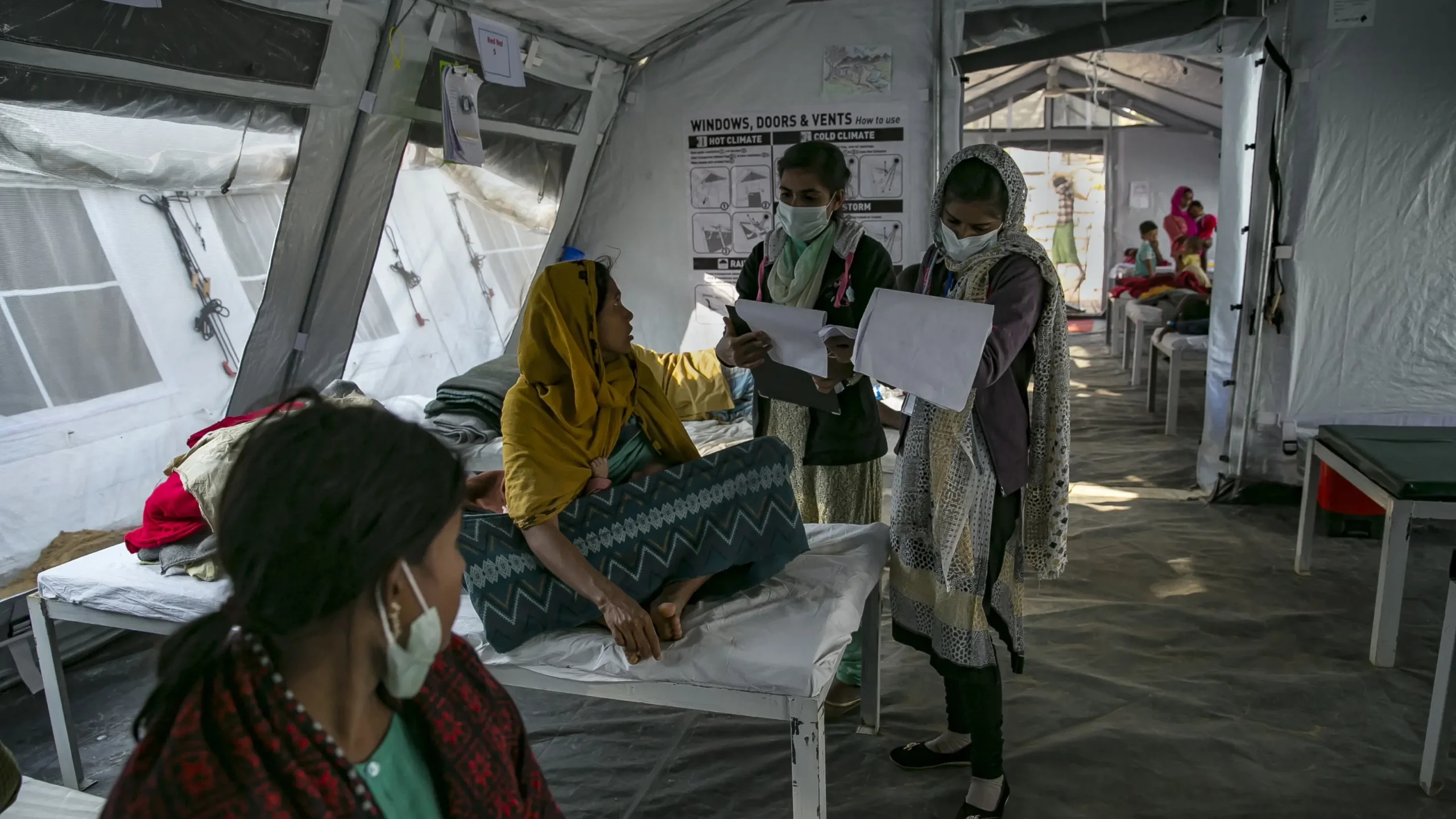

Staff meeting to discuss preparedness activities. Courtesy of Gifty Ofori Ansah

References

- World Health Organization. Lassa Fever. https://www.who.int/health-topics/lassa-fever

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014) Lassa Fever: Signs and Symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/lassa/symptoms/index.html

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Lassa Fever. https://africacdc.org/disease/lassa-fever/

- Naeem A, Zahid S, Hafeez MH, Bibi A, Tabassum S, Akilimali A. (2023) Re-emergence of Lassa fever in Nigeria: A new challenge for public health authorities. Health Sci Rep. 24;6(10):e1628. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1628

- Mariam Ileyemi. (2024, February 8) Lassa Fever: Nigeria records over 1,000 infections, 219 deaths in 2023. Premium Times. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/657102-lassa-fever-nigeria-records-over-1000-infections-219-deaths-in-2023.html

- Resolve to Save Lives. (2024) Rapid Outbreak Financing. https://etdh.resolvetosavelives.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Rapid-Outbreak-Financing-to-Prevent-Epidemics-March-2024.pdf