Epidemics that didn't happen

Avian Influenza in Finland

Human and animal health authorities joined forces to bring an outbreak under control with no human cases.

About H5N1

Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1, commonly known as “bird flu”, is a very contagious animal disease that causes mass die offs in both domesticated poultry flocks and wild birds. Outbreaks are happening more often globally—and with devastating consequences to animal and human health, economic security, international trade, conservation efforts and food security.1 In 2022 alone, 67 countries on 5 continents reported outbreaks in wild or domesticated birds and more than 131 million domesticated poultry died or were culled as part of efforts to contain the virus’ spread.2 The ongoing panzootic (the animal equivalent of a pandemic) affecting dairy farms across the United States started in 2022 and is showing more evidence of interspecies transmission than past outbreaks and is affecting a wider geographic range.

Although avian influenza viruses are adapted to transmit within bird populations, spillover events to mammals, including humans, have been recorded.34 In humans, the virus causes lower respiratory infections leading to fever, cough, shortness of breath, and pneumonia—and is much deadlier than seasonal flu strains.56 The majority of cases reported in humans have occurred in people with direct exposure to sick or dead birds, most typically through commercial farming, backyard poultry or at wild bird markets.4

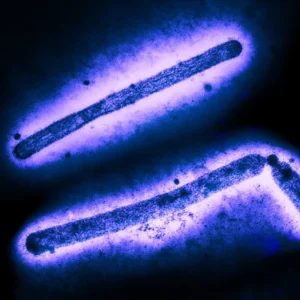

Virus Image: Three influenza A (H5N1/bird flu) virus particles. Credit: CDC and NIAID

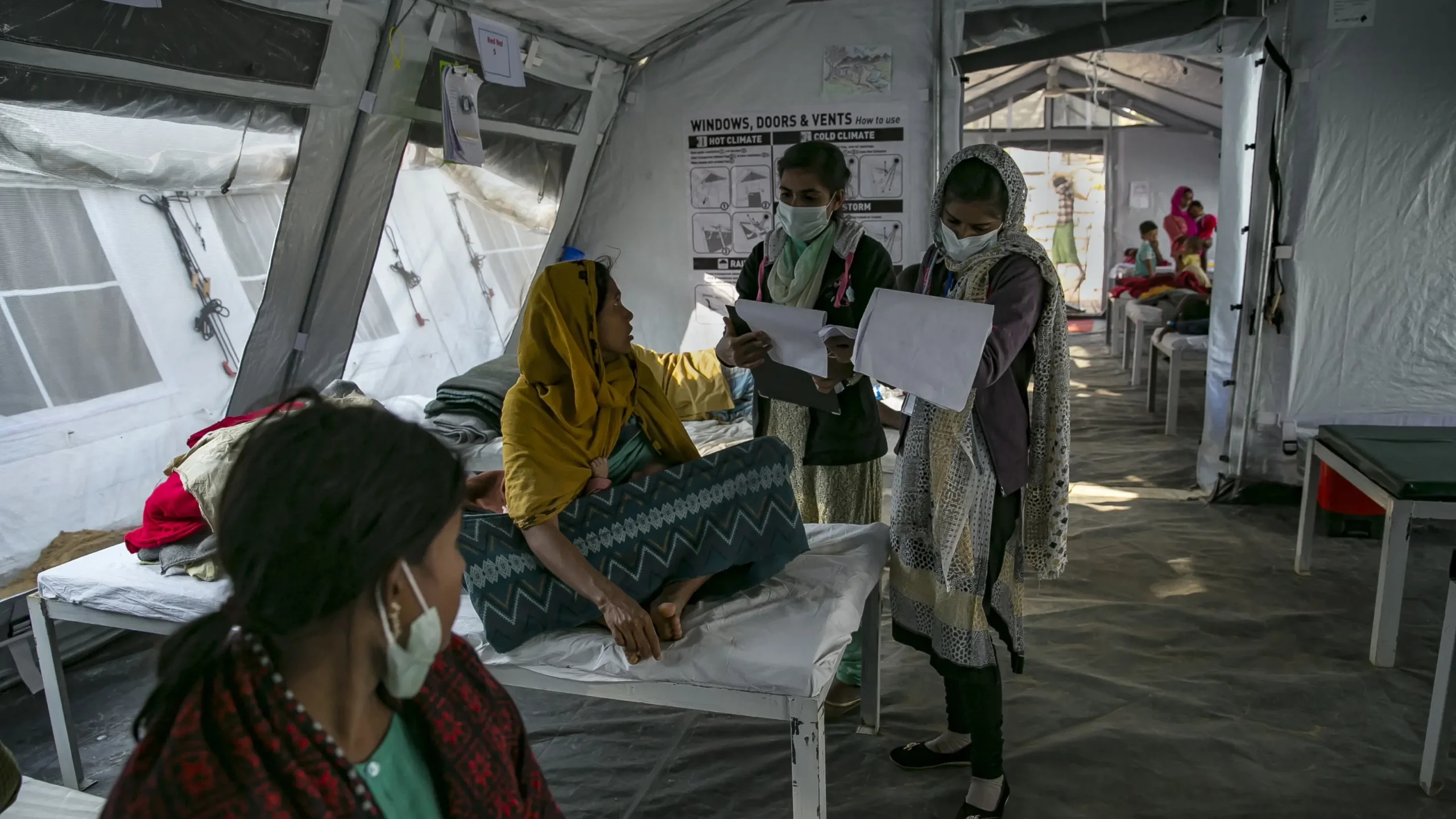

Header: Fur farm in Ostrobothnia, Finland. Credit: Eva-Stina Kjellman, Wikström Media (CC BY-SA 3.0)

H5N1 is much deadlier than seasonal flu strains, with over 50% of infected people dying.

A flock of Barnacle geese fly over a field in Parikkala, Finland. Credit: ALESSANDRO RAMPAZZO via Getty Images

A flock of Barnacle geese fly over a field in Parikkala, Finland. Credit: ALESSANDRO RAMPAZZO via Getty Images

What Happened

On July 12, 2023, the Finnish Food Authority (FFA) was alerted to a deadly outbreak on a fur farm in western Finland. Earlier that year, FFA had launched a surveillance program out of concern that ongoing outbreaks of avian influenza in wild birds could spill over into mammals, with particular risk to those raised for fur. As part of that program, a fur farmer who identified symptoms and unexpected deaths among his animals sent samples to a laboratory, and the laboratory immediately notified FFA. On July 13, testing confirmed the samples were positive for highly pathogenic H5N1. Within a week, samples submitted by four additional farms also tested positive, with seven additional farms shortly after.

A rising number of H5N1 cases in mammals, including animals farmed for fur, such as minks, has sparked concerns that the virus could adapt to infect mammals, including humans, more easily. And because mammals can be vulnerable to infection from both avian and human influenza viruses at the same time, they can act as “mixing vessels” to produce novel hybrid strains. The Quadripartite—a partnership including the United Nations, World Health Organization and World Organisation for Animal Health—has called for countries to work across sectors to better protect animals and humans from such threats.11

Farmed mink in Finland. Credit: Oikeutta eläimille via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Within two weeks, animal health officials had confirmed cases of infected mink, foxes, and raccoon dogs at 20 different farms, each housing anywhere between 600 and 50,000 animals.8 Such large outbreaks occurring in the confines of fur farms, where genetically similar animals are kept in large numbers and tight quarters, creates opportunities for the virus to infect the animals’ human handlers—which is a particular concern if the infected mammals produce a novel strain that can spread more readily between mammals or humans. This rapidly spreading outbreak raised alarm bells among Finland’s human and animal health authorities.

The Response

Within 24 hours of the first case being confirmed in a mammal, FFA reported the outbreak to the World Organisation of Animal Health and alerted its human health counterpart, the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Because of the risk of human spillover, and the pandemic potential of any novel influenza A virus of animal origin that is distinct from seasonal influenza A viruses, it’s particularly important for human health agencies to be notified immediately so they can start their surveillance efforts, including testing at-risk people working on infected farms.

FFA and THL frequently collaborate in outbreak response efforts, and they convened a multidisciplinary team of human and animal health experts to launch a rapid joint response. When the outbreak began, they met twice weekly to share their contingency plans and align on their response actions, an ongoing partnership that allowed the two teams to effectively combine forces for a successful response effort.

FFA and THL convened a multidisciplinary team of human and animal health experts to launch a rapid joint response.

Black-headed gulls foraging on farmland. Credit: Traveller MG/Shutterstock

Black-headed gulls foraging on farmland. Credit: Traveller MG/Shutterstock

Working with the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, the team immediately started advising farms through the Finnish Fur Breeders’ Association, which rapidly disseminated information to its more than 500 member farms about how to detect infected animals, protect workers from infection, and prevent the further spread of the virus. THL also supported FFA to set up whole genome sequencing to track any mutations in the virus and developed protocols to help protect health care workers treating suspected human cases and laboratory personnel testing samples.

But the response quickly hit a snag. FFA didn’t have the legal authority to order the culling of infected animals—a critical prevention measure to stop the further spread of the disease—because of how the disease is categorized under Finnish law. FFA had, however, previously discussed the need for new legislation with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry just a few months before the outbreak. In the intervening months, the Ministry had drafted legislation granting FFA the required authority, which it enacted less than one week after the first positive case.9

On July 28, FFA ordered mass culling of infected mink, which posed the greatest risk of transmitting the virus to humans. When it became clear that foxes and raccoon dogs on the fur farms also posed a risk, they extended the cull orders to also include these animals on affected farms. Over the course of the outbreak, half a million animals on 71 farms were culled. The process of culling animals causes immense emotional and financial stress to farmers and communities. The new categorization of the disease in the legislation ensured that farmers could be reimbursed for the value of culled animals. Veterinarians visiting the farms as part of the response team also played an important role for human health by advising on protective measures. They also sent questionnaires to people exposed to animals to make sure they could be tested if needed. No human cases were detected.

Finland’s response efforts serve as a prime example of One Health in action.

Left: Finnish fur farm enclosure.

Below: Winter snow on a Finnish fur farm.

All photos courtesy of Anna-Maria Moisander-Jylhä

Above: Finnish fur farm enclosure.

Below: Winter snow on a Finnish fur farm.

All photos courtesy of Anna-Maria Moisander-Jylhä

Strong collaboration between human and animal health officials proved pivotal to allowing a rapid and robust response to the H5N1 outbreak on the fur farms. “We have a long tradition of a multisectoral, ‘One Health’ approach in Finland,” said Terhi Laaksonen, director of the animal health and welfare department of the FFA, describing a philosophy that emphasizes the interconnected nature of human, animal and environmental health. “Our animal and human health sectors have been working closely together for twenty or thirty years.”

On January 15, 2024, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry passed additional regulations requiring farms to implement biosecurity measures, including the use of netting to protect fur animals from exposure to wild birds. Most fur farms in the country house their animals in cages under shade structures with open sides. Without nets or other barriers, wild birds can easily enter the structures beneath the fur animals’ cages or shadow houses, potentially exposing them to viruses. Genetic sequencing suggested that the H5N1 in this outbreak initially spread from wild birds to fur animals, though veterinary officials note it may have subsequently spread between fur animals and some farms via other routes.8 The new legislation intends to minimize the possibility of wild birds entering enclosures and, therefore, minimize the risk of future outbreaks.

Although the exact risk of viral transmission from fur animals to humans is not well understood, Finnish One Health officials used this outbreak as an opportunity to implement robust control measures to limit human exposure to the virus, and therefore the possibility of human cases in farm workers and those involved in response efforts. They also tested exposed people and found no evidence of human H5N1 infection during the outbreak. But the virus continues to spread among wild bird populations globally. With the annual spring migration of wild birds bringing new bird flocks to Finland every year, FFA and THL are continuing to strengthen their ongoing partnership to help prevent the further spread of H5N1, and ultimately keep their communities safe.

Aisling Vaughan, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the World Health Organization, said: “Finland’s response efforts serve as a prime example of One Health in action, demonstrating how a strong foundation of trust among stakeholders enables rapid information exchange, coordinated multisectoral efforts and decisive actions to effectively prevent further virus spread and safeguard both human and animal health.”

We have a long tradition of a multisectoral, ‘One Health’ approach in Finland. Our animal and human health sectors have been working closely together for twenty or thirty years.

Terhi Laaksonen, Finnish Food Authority

Enablers

Rapid detection, notification and early response actions

Timeline

Emergence

Detection & Notification

Response

Control

Finland’s response efforts serve as a prime example of One Health in action, a strong foundation of trust among stakeholders enables rapid information exchange, coordinated efforts and decisive actions to effectively prevent further virus spread and safeguard both human and animal health.

World Health Organization

Finland’s response efforts serve as a prime example of One Health in action, a strong foundation of trust among stakeholders enables rapid information exchange, coordinated efforts and decisive actions to effectively prevent further virus spread and safeguard both human and animal health.World Health Organization

References

- Xie, R. et al.(2023) The episodic resurgence of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 virus. Nature. 622 (1) 810–817. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06631-2

- World Health Organization. (2023) Ongoing avian influenza outbreaks in animals pose risk to humans. https://www.who.int/news/item/12-07-2023-ongoing-avian-influenza-outbreaks-in-animals-pose-risk-to-humans

- Agüero, M. et al. (2022) Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in farmed minks, Spain. Eurosurveillance. 28 (3) 2300001. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2023.28.3.2300001.

- Peiris, J.S., de Jong, M.D., Guan, Y. (2007) Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (2) 243-67. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00037-06.

- World Health Organization.(2007). Update: WHO-confirmed human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) infection, 25 November 2003-24 November 2006. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/240862/WER8206_41-47.PDF.

- Xie, Y., Choi, T., Al-Aly, Z. (0223) Risk of Death in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 vs Seasonal Influenza in Fall-Winter 2022-2023. 329 (19) 1697–1699. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.5348.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. (2005) The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22148/

- Lindh, E. et al. (2023) Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection on multiple fur farms in the South and Central Ostrobothnia regions of Finland, July 2023. 28 (31) 2300400. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.31.2300400.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland. (2023). Finland intensifies measures to combat avian influenza at fur farms. https://mmm.fi/en/-/finland-intensifies-measures-to-combat-avian-influenza-at-fur-farms

- World Organisation for Animal Health. (2023) Statement on avian influenza and mammals. https://www.woah.org/en/statement-on-avian-influenza-and-mammals/.

- World Health Organization. (2023) Quadripartite call to action for One Health for a safer world. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-03-2023-quadripartite-call-to-action-for-one-health-for-a-safer-world.