Epidemics that didn't happen

Cholera in Bangladesh

Decades of effort paid off when a successful response prevented an outbreak from exacerbating a refugee crisis.

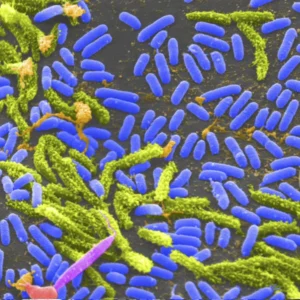

About Cholera

Cholera is a disease caused by infection of the intestine by Vibrio cholerae bacteria. The disease is usually spread by eating or drinking contaminated food or water, and it can kill in hours if left untreated. There are an estimated one to four million global cases per year and, despite being easily preventable and treatable, cholera is responsible for up to 143,000 deaths each year.1

It typically takes 12 hours to five days for people infected to present symptoms, which can include watery diarrhea, vomiting, fatigue and thirst. In most cases, symptoms are mild enough to be treated with oral rehydration solutions. However, even mild cases of cholera can spread widely, as those infected continue to shed the bacteria up to 10 days after infection. Severe cases are much more dangerous, as more intense symptoms can lead to rapid loss of body fluids, dehydration and shock, requiring treatment with intravenous fluids and antibiotics.1

Virus Image: Rod-shaped Vibrio cholera bacteria. Credit: Tina Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Header: People walk through a marketplace in a Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Credit: Allison Joyce via Getty Images

Despite being easily preventable and treatable, cholera is responsible for up to 143,000 deaths each year.

Flooding in Bangladesh following heavy rains. Credit: amdadphoto/Shutterstock.

The current cholera pandemic began in South Asia in 1961 and has surged in recent years following years of decline.2 Safe water, basic sanitation and good hygiene (“WASH”) all form a critical part of infection prevention and control, but these measures aren’t always in place, particularly in resource-strapped areas and those experiencing conflict and unplanned urbanization. An oral vaccine exists but global supply has been in shortage, in part because there’s only one manufacturer currently producing vaccines for global use.8 The shifting climate, meanwhile, also presents an increasing risk of cholera in many areas.1

Bangladesh, for example, is a cholera-endemic country with one of the world’s highest burdens of the disease,2 a problem that is compounded by an ongoing refugee crisis and frequent flooding. In 2017, the Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and its partners completed one of the largest cholera vaccination campaigns in history, delivering some 900,000 doses to at-risk communities in the border region of Cox’s Bazar, where hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees have fled from neighboring Myanmar.3 Cholera outbreaks present an ongoing threat to displaced people living in refugee camps.

There is a strong possibility of cholera transmission in the camps because of the sheer density of people living in these areas, and the years of privation they’ve had to endure.

David Otieno, World Health Organization

What Happened

The Rohingya people have been fleeing Myanmar since 1982.11 After the largest exodus in 2017, there are now some 960,000 Rohingya refugees living across 33 temporary camps in Cox’s Bazar—collectively the world’s largest refugee camp.9 This humanitarian crisis is ongoing and growing, according to David Otieno from the Sub Office of WHO Bangladesh in Cox’s Bazar, who leads the Epidemiology and Surveillance Team supporting the camps and the surrounding Bangladesh population: “There is a strong possibility of cholera transmission in the camps because of the sheer density of people living in these areas, and the years of privation they’ve had to endure.”

The team is part of a massive humanitarian effort that’s been striving to provide people in the camps with access to basic facilities for several decades. In Cox’s Bazar, cholera is a high priority for UN agencies like the International Organization for Migration, WHO, and various NGOs including Doctors Without Borders, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and its local chapters. Collectively, these institutions have worked tirelessly to run vaccination campaigns, provide water and sanitation solutions and create treatment facilities for managing suspected and confirmed cholera cases, to lay a solid foundation to make sure the camps are best prepared to protect people from ongoing infectious disease outbreaks. Many of these partners follow a WHO-led “multisectoral acute watery diarrhea/cholera preparedness and response plan”, which was developed to facilitate effective resource mobilization in response to outbreaks following a wave of displacement in 2018.

Teams supporting the camps remain on high alert throughout the year to detect and investigate any signs of a new outbreak.

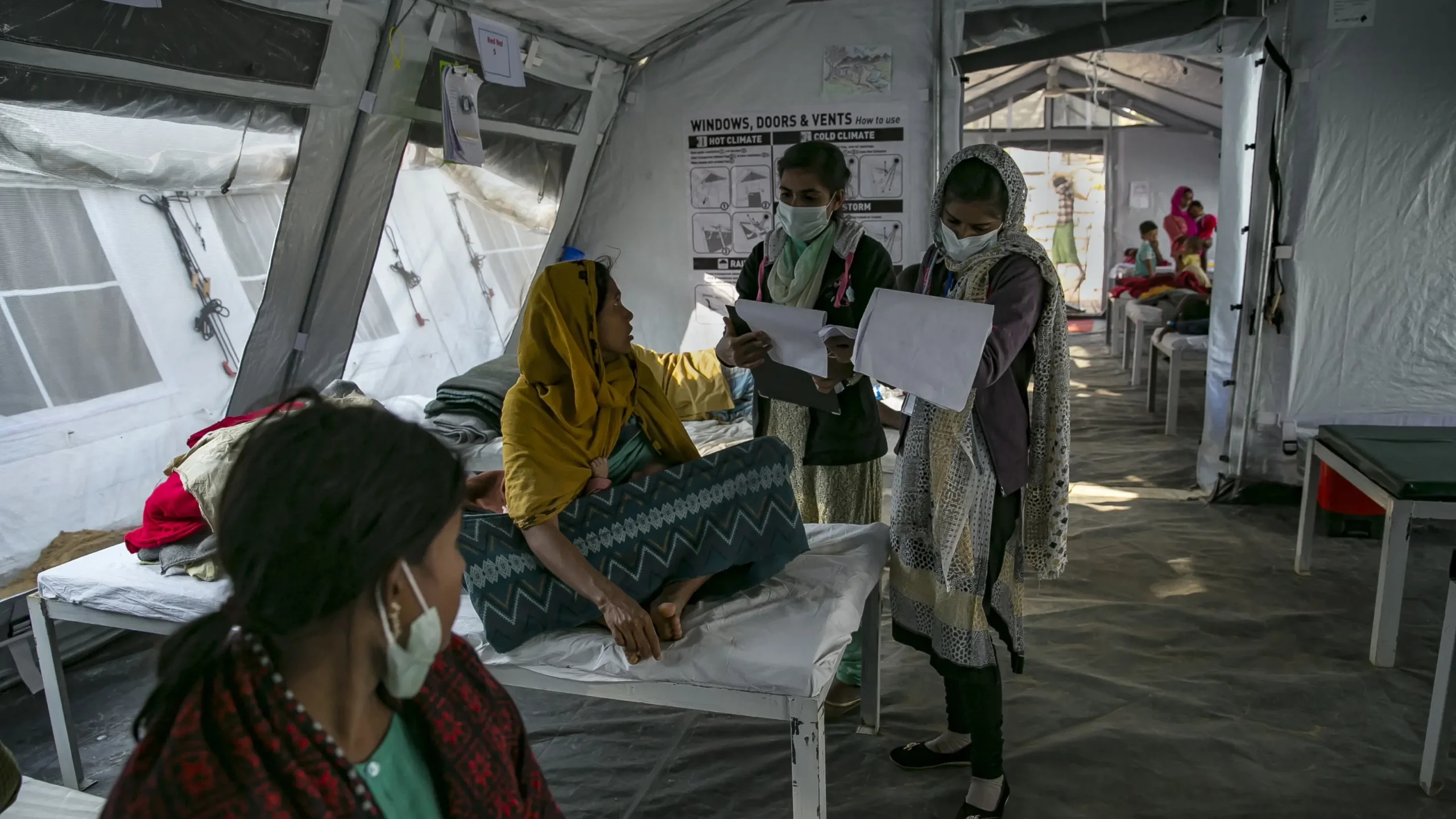

An outbreak response team in Cox’s Bazar. Courtesy of Feroz Khan

Since cholera is endemic to Bangladesh, and because those living in the camps are at particular risk, cholera outbreaks occur regularly throughout the year—and teams supporting the camps remain on high alert throughout the year to detect and investigate any signs of a new outbreak. Since 2017, the humanitarian effort in Cox’s Bazar has been mediated through “early warning, alert and response”, or EWARS, a system for managing detection, notification and response to outbreaks created by WHO’s Health Emergencies Program. EWARS allows real-time reporting from the frontlines, including locations without internet access. If a clinician suspects a case, they can notify the system through their cell phone, which kickstarts a set of alerts that ultimately allows surveillance teams and laboratories to coordinate with clinicians and mount a response.

On March 25, 2023, cases of cholera in Cox’s Bazar started to surge with two confirmed and an additional two suspected cases, which camp health workers logged through the EWARS system. Just three days later, that number spiked to 10 confirmed cases and, by the end of the week, there were 31 confirmed cases—the highest weekly increase seen in the area since the huge influx of refugees in 2017. Through EWARS, the WHO Epidemiology and Surveillance Team was able to sound the alarm to local laboratories and national-level public health officials and begin analyzing where, exactly, the cases were coming from.

The Response

Within 24 hours of any suspected or confirmed case of cholera in one of the camps, a “joint assessment and response team” receives an alert through EWARS, including available information about the case to begin their investigation, including critical details about the patient and location. In Cox’s Bazar, each joint assessment and response team includes one WASH expert and one health expert capable of rapidly testing for the disease in the field. The teams visit households and other relevant locations to identify possible causes and put protective measures in place.

An outbreak response team gathers samples for testing. Courtesy of Feroz Khan

Over the course of a week, these teams visited the hotspot and each affected household, gathering water samples for testing and providing water treatment pills and essential hygiene recommendations to affected families and their neighbors, meanwhile anyone who tested positive was kept in isolation at one of the camps’ health facilities. As suspected cases surged during that week, the teams redoubled their efforts to confirm the cases and keep people safe, while also taking a step back to plot and analyze the distribution of cases to figure out what might be the root cause.

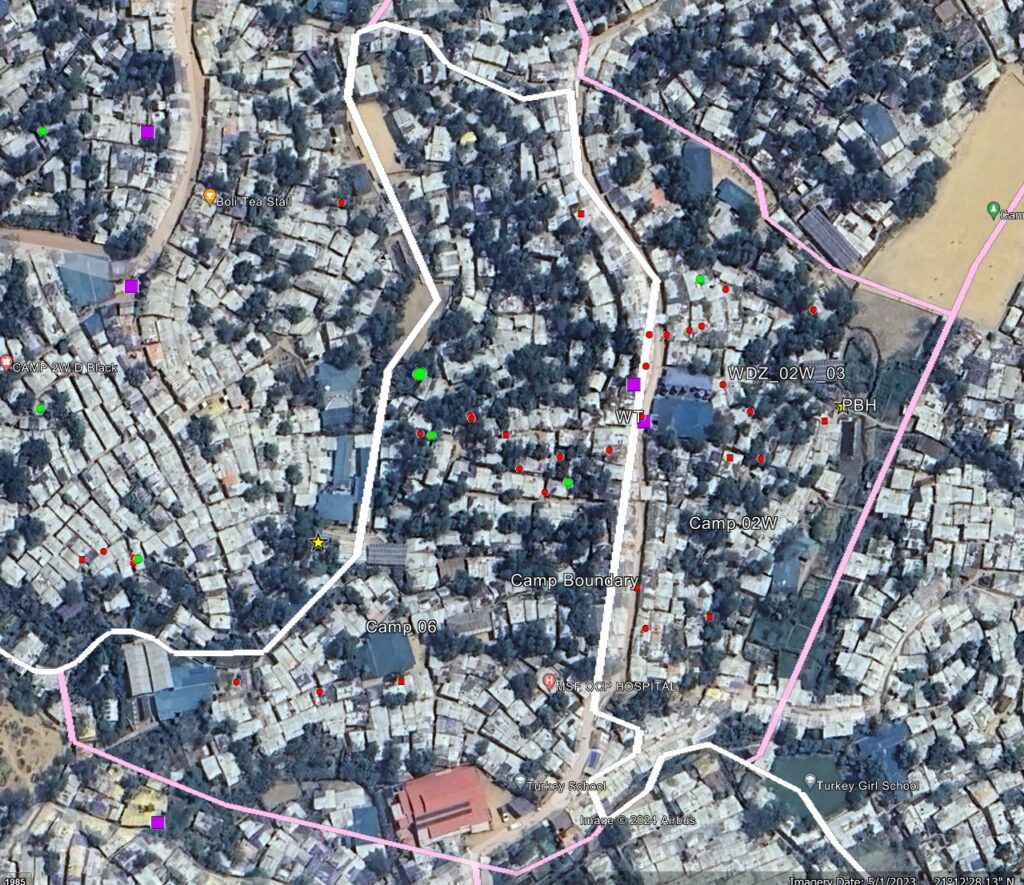

It turned out that 72% of cases came from just two adjacent camps. “Despite coming from two different camps, we were dealing with one single cluster of cases,” said Julien Graveleau, the WASH Sector Lead at UNICEF who supported the response. “By plotting the outbreak, we could see that the cases matched perfectly with a water supply network that was serving both camps. It’s extremely unusual for two camps to share a single water source, and this led us to suspect that the water source could be responsible for the surge in cases.”

By plotting the outbreak, we could see that the cases matched perfectly with a water supply network that was serving both camps.

Julien Graveleau, UNICEF

Above: Map of water distribution network in Cox’s Bazar refugee camps.

Above: Visiting households to gather samples for testing.

Below: Water station in Cox’s Bazar refugee camp.

All photos courtesy of Julien Graveleau

Left: Map of water distribution network in Cox’s Bazar refugee camps.

Right: Visiting households to gather samples for testing.

Below: Water station in Cox’s Bazar refugee camp.

All photos courtesy of Julien Graveleau

By testing the water being used in the two camps, the WASH Sector Team soon discovered that it contained no detectable chlorine. Chlorine effectively and affordably disinfects water, thereby preventing cholera transmission4—and all water is supposed to be chlorinated before it reaches the camps. According to the WASH Sector Team, the water supply system is fragmented and, as a result, the availability and quality of water provided to different camps has been suboptimal. The team immediately contacted the Department of Public Health Engineering and tasked them with contacting the private contractor responsible for chlorinating this particular water source. The team then provided the contractor with chlorine to treat the water supply and, within days, the number of cases began to drop—confirming their suspicions of the underlying cause.

The Epidemiology and Surveillance Team at WHO Bangladesh’s Sub Office, together with its large community of humanitarian partners, also runs cholera vaccination campaigns every two to three years, based on the availability of vaccines and the duration of immunity it affords. Their last campaign took place in 2021—it was a huge success, and around 86% of the Rohingya refugees living in the camps took part. The team suspects that the surge in cases witnessed in 2023 is perhaps not surprising given that immunity had likely waned since the last vaccination campaign. The camps have also seen an influx of many new refugees who have not yet had the opportunity to be vaccinated, in addition to new children being born in the camps.

The WASH Sector Lead, meanwhile, speculates that unusual rainfall might have played an important role: “March is our dry season—we usually have no rain whatsoever. But about 10 days before we started recording an increase in cholera cases, we had sudden heavy rains in the area. While we can’t say for sure, it’s possible this unexpected rain led to a nearby fecal sludge treatment plant overflowing into the water supply and thus contaminating the water.” The speculation could also explain why this outbreak occurred several months earlier than seasonal surges in previous years. And with the frequency and intensity of rains in Bangladesh expected to increase,5 outbreak prevention strategies that include responding to environmental triggers before a surge in cases could prove pivotal in years to come.

After a rise in cases beginning on March 25, 2023, cholera cases in Cox’s Bazar peaked at 31 cases a week later by April 1. During that time, AWD and Cholera Joint Assessment and Response Team (JART), a multisectoral rapid response structure based at the camp level and comprising WASH and health sector partners, initiated rapid risk assessment and field investigations in the affected camps to identify sources and modes of transmission to contain the outbreak, built on decades of ongoing work in the camps with additional response measures—including isolating patients, providing WASH services and chlorinating water—and, by April 8, cases started to decline.

The WHO Epidemiology and Surveillance Team quickly teamed up with JART within 48 hours of verification of acute water diarrhea (AWD) events and were able to identify the source of contamination from the results of field epidemiological and environmental investigation complemented with the bacteriological and physiochemical analysis done on water samples from suspected domestic water sources. The untreated water supply line maintained by the government’s department was identified and linked to the clusters of cases reported and immediately chlorinated and affected families were provided with Aquatabs by the WASH Sector while the Health Sector and Ministry of Health coordinated appropriate and timely management of cases at community and those at AWD Isolation facilities. By April 15, cases dropped to baseline levels. In the absence of timely interventions, cases could have been almost five times higher.10

The government counterpart acknowledged the established and current disease containment drives and expressed their appreciation for building community trust through a set of interventions to be followed. The Office of the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner stated: “The ongoing activities with fighting against cholera has enhanced fostered level of trust and confidence between the refugee population and health sector partners including other humanitarian actors in Rohingya refugee camps and this will contribute immensely to improved community ownership of services delivered in camps.”

At the national level, Bangladesh continues to experience biannual outbreaks,6 which the WHO-hosted Global Task Force on Cholera Control aims to eliminate by 2030.2

In the absence of timely interventions, cases could have been almost five times higher.

Enablers

Timeline

Emergence

Detection & Notification

Response

Control

References

- WHO. (2023). Cholera. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera.

- Global Task Force on Cholera Control. (2019). National Cholera Control Plan (NCCP) for Bangladesh 2019-2030. https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/national-cholera-plan-bangladesh.pdf.

- UNICEF. (2017). World’s second largest oral cholera vaccination campaign kicks off at Rohingya camps in Bangladesh. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/worlds-second-largest-oral-cholera-vaccination-campaign-kicks-off-rohingya-camps.

- CDC. (2016) Notes from the Field: Chlorination Strategies for Drinking Water During a Cholera Epidemic — Tanzania, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6541a6.htm

- Alam, E., et a (2023) Climate change in Bangladesh: Temperature and rainfall climatology of Bangladesh for 1949–2013 and its implication on rice yield. PLoS One. 18 (10) e0292668. https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0292668.

- Global Task Force on Cholera Control. (2016). Control of Endemic Cholera in Bangladesh: Update the existing cholera investment case, surveillance and developing the funding consortium. https://www.gtfcc.org/research/control-of-endemic-cholera-in-bangladesh-update-the-existing-cholera-investment-case-surveillance-and-developing-the-funding-consortium/.

- WHO. (2022). Cholera – Global situation. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON426.

- Reuters. (2024). Cholera vaccine stocks ’empty’ as cases surge. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/cholera-vaccine-stocks-empty-cases-surge-2024-02-14/.

- USA for UNHCR. (2023). Rohingya Refugee Crisis Explained. https://www.unrefugees.org/news/rohingya-refugee-crisis-explained/.

- Personal communication. (2024). Dr. Muhammad (Feroz) Khan, World Health Organization.

- Human Rights Watch. Rohingya. https://www.hrw.org/tag/rohingya.