Epidemics that didn't happen

Dengue Fever in Somalia

Local community volunteers worked with public health experts to protect themselves and their neighbors.

About Dengue

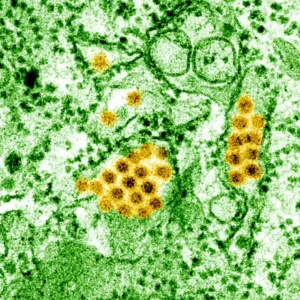

Dengue fever is a viral disease transmitted to humans through mosquito bites. It is endemic in over 100 countries—and leads to an estimated 400 million infections and 20,000 deaths each year, most of them in children.1 Although it’s historically been confined to the tropics, climate change is allowing Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector of the virus, to migrate increasingly northward. In recent years, cases have been reported globally, with a record surge reported in the Americas.

Many cases are asymptomatic or mild and can be treated at home with over-the-counter pain medications. Symptoms include headache, nausea, fever and severe joint pain, which is why dengue is known as “breakbone fever.” These symptoms typically last one to two weeks, and around 5% of those infected develop severe dengue, which requires hospitalization. Severe dengue can cause bleeding or organ damage, which can be fatal if left untreated.

Virus Image: Dengue virus particles. Credit: CDC and NIAID

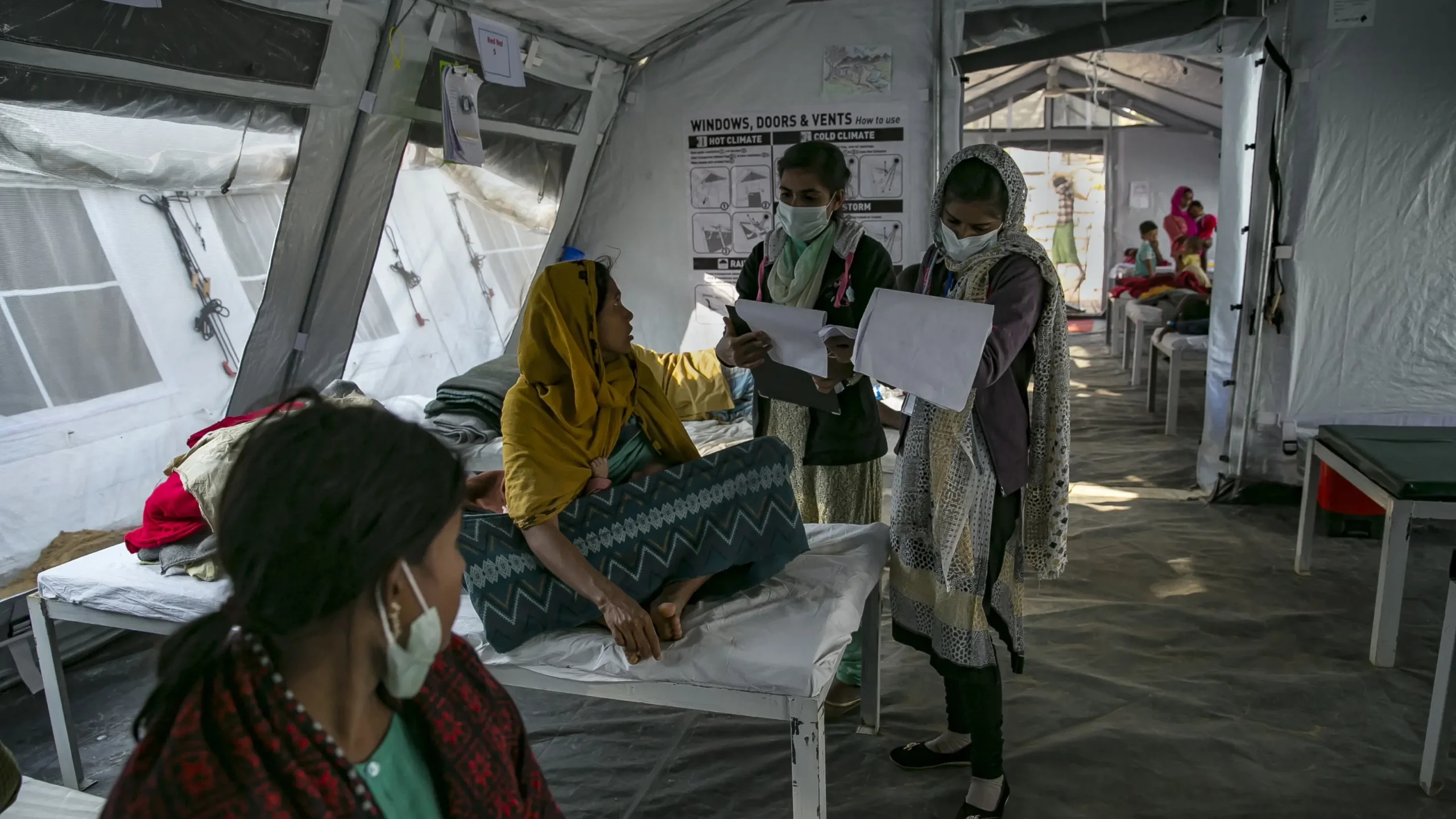

Header: Engaging with local community stakeholders. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

Dengue is on the rise globally—there are now an estimated 400 million infections each year, causing some 20,000 deaths.

A mosquito of the Aedes genus. Aedes aegypti mosquitos are the primary carriers of dengue. Credit: Teerapong mahawan/Shutterstock

A mosquito of the Aedes genus. Aedes aegypti mosquitos are the primary carriers of dengue. Credit: Teerapong mahawan/Shutterstock

Unlike some other disease-causing species, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are most active during the day, making bed nets an ineffective prevention tool for dengue fever. Effective prevention measures include draining mosquito breeding sites, which tend to be areas of stagnant water, covering as much skin as possible to minimize the risk of bites, using mosquito repellents, and installing window screens in homes and other buildings. But implementing preventative measures can be very difficult, and thus outbreaks continue worldwide.

What Happened

On December 27, 2022, in the small village of Ga’nafale in Somalia’s Mudug region, a community volunteer from the Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS) identified several residents with fever and rash, as well as more unusual symptoms including bleeding from the nose and vomiting blood.3 The volunteer recorded these observations using Nyss, a software platform that enables real-time collection and notification of suspected public health risks, data management and analysis. Nyss is used by the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement across the globe to support community-based surveillance efforts.

Investigation by Somalia’s Ministry of Health confirmed that many of these cases were measles—one of the only diseases the village was equipped to test for at the time—but three cases were not. Although diagnostic tests for dengue are available through laboratory networks, there were none available in the village at the time of this outbreak. Fortunately, the cluster of unusual symptoms allowed the volunteer to suspect dengue, make a clinical diagnosis and initiate public health control measures. Through Nyss, the volunteer’s signal was immediately forwarded to the district level authorities of the Ministry of Health, which held a meeting to discuss its plans for a response that same day.

Nowadays, Dengue is becoming even more common than malaria.

Mohamud Abdi, Norwegian Red Cross

Campaign to remove mosquito breeding sites. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

The Response

On December 29, 2022, just two days after these suspected cases were reported, a rapid response team arrived in Ga’nafale to investigate. This included public health officials and SRCS staff. The team was primed to manage these new cases following recent dengue outbreaks in neighboring areas,2 meanwhile local health workers and volunteers had already been trained to look for and report on cases showing symptoms of suspected dengue through ongoing collaborations with the community.

We trained our communities to detect and report a wide range of symptoms because we want them to detect emerging diseases.

Julia Jung, Norwegian Red Cross

Engaging with local community stakeholders. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

Engaging with local community stakeholders. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

“We train our communities to detect and report a wide range of symptoms, even if they cannot conclusively diagnose a disease, because we want them to detect emerging threats,” says Julia Jung, Regional Technical Advisor for Public Health for the Norwegian Red Cross in Africa. The Norwegian Red Cross has been working in partnership with the SRCS in Somalia’s Puntland State since 2020. “A recent dengue outbreak in neighboring Somaliland developed into a large-scale epidemic. In Puntland, where this outbreak occurred, our communities were much better prepared to stop the outbreak.”

The team of experts, in partnership with local community leaders, acted quickly to prevent the further spread of the disease into a large-scale outbreak. SRCS volunteers in the affected villages and nearby surrounding areas identified and mapped potential mosquito breeding sites. This included open wells, ponds, and sewers which were later treated or covered, as well as pools of stagnant water accumulating around dwellings that were drained to remove the water. Eliminating Aedes aegypti’s potential breeding sites was an important part of the response that resulted in fewer mosquitoes able to carry the disease in the days that followed.

In addition to implementing these preventive measures to control mosquito infestation, the volunteers also carried out an extensive educational campaign—and encouraged community members to spread the message across their networks and encourage more people to connect with the response team. They advised people in the area to keep themselves and each other safe, including bite avoidance strategies, medications to avoid that can exacerbate dengue symptoms, and how to spot and remove mosquito breeding sites. SRCS also broadcasted awareness messages through popular local radio stations in an effort to reach people in more remote locations.

Engaging with local community stakeholders. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

Community leaders, health workers and volunteers encouraged their communities to spread the message as widely as possible.

Left/Below: Engaging with local community stakeholders. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

Above/Below: Engaging with local community stakeholders. Courtesy of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

Enablers

Mohamud Abdisalam, the SRCS community-based surveillance officer in Mudug region, noted that until recently, dengue was relatively uncommon in Somalia. “Just a few years ago, our clinical staff was mostly dealing with cases of malaria. Nowadays, dengue is becoming even more common than malaria.” Somalia is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world,4 and rising temperatures, along with erratic heavy rainfall, present growing risks that could result in additional dengue outbreaks in the years to come.”

Mahad Yusuf, the community health manager at SRCS for Puntland State, speculates that El Niño, a warming of the ocean surface potentially being made stronger by climate change, may have contributed to the surge in dengue cases witnessed in many parts of the country that year: “Mudug region was greatly affected by flooding that rainy season, which increased the number of mosquito breeding sites,” he says. With these conditions expected to occur more frequently in the future, Yusuf adds that it’s critical to anticipate outbreaks based on weather patterns and flooding events and implement appropriate prevention measures.

No further cases were found in Ga’nafale after this response effort, but the outbreak was not officially declared over because of cases in the wider region. Although seasonal upticks in dengue fever continue to be a problem in Somalia and other countries where the disease is endemic, the outbreak response in Ga’nafale illustrates how community-based surveillance efforts can provide invaluable early warnings and how community health services can empower communities to protect themselves and minimize the number of people affected by the disease.

It’s critical to anticipate outbreaks based on weather patterns and flooding events and implement appropriate prevention measures.

Rapid detection, notification and early response actions

Active role of community in surveillance and response actions

Risk communication and community engagement

Multisectoral response leading to removal of mosquito breeding sites

Timeline

Emergence

Detection

Notification

Response

Control

The outbreak response in Mudug illustrates how community-based surveillance efforts can empower communities to protect themselves and minimize the number of people affected by the disease.

Mahad Yusuf, Somali Red Crescent Society

References

- World Health Organization. (2023). Health Emergency Programme Update – Somalia. https://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/somalia/Health-Emergency-Programme-Update-October-2023.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Situation updates for Cholera, Dengue & suspected Diptheria in Somalia. https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/situation-updates-cholera-dengue-suspected-diptheria-somalia-who-emergencies-program-nov-2023.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (2023). Detection of dengue fever outbreak at Ga’nafale village in Mudug region. https://cbs.ifrc.org/news/detection-dengue-fever-outbreak-ganafale-village-mudug-region.