Epidemics that didn't happen

Leptospirosis in Vanuatu

Despite being hit by two cyclones that wrecked critical infrastructure, health agencies minimized disease spread and protected communities.

About Leptospirosis

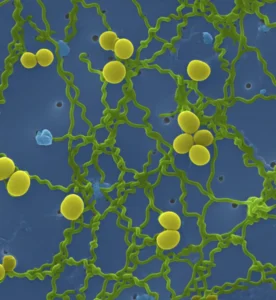

Leptospirosis, caused by the Leptospira bacteria, is one of the world’s most common and widely spread zoonotic diseases of epidemic potential.12 Humans typically contract the disease through direct contact with or being in an environment contaminated by infected animals’ urine, such as standing water associated with farming activities or when extreme rainfall causes flooding. Many species of domestic and wild animals can be infected and shed bacteria. Human to human transmission is possible, but rare.3

Infections can be easily treated with antibiotics if caught early, but the disease is challenging to diagnose in its early stages because symptoms–including fever, muscle aches, chills and abdominal pain–mimic many other common conditions. While the disease begins with mild flu-like symptoms, it can progress to severe disease with lung hemorrhaging and the inability to breathe and, in some outbreaks, mortality is higher than 10%.3 Timely diagnosis is a particular problem in rural areas where people don’t have access to care—which are also the places where outbreaks are most likely to occur.

Virus Image: Credit: Tina Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa (CC-BY 2.0)

Header: Women walking on Malo Island, Vanuatu. Credit: Nina Janesikova/Shutterstock

Timely diagnosis is a particular problem in rural areas where people don’t have access to care—also the places where outbreaks are most likely.

Woman in Vanuatu holding onto her pet pig. Credit: Abi Sawell/Shutterstock

More than 500,000 human cases of leptospirosis are thought to occur annually worldwide.3 The disease is endemic in humid tropical and subtropical climates because the bacteria survive longer in warm, humid environments.2 Epidemics are common when such environments experience heavy rainfall or flooding,3 and the increasing incidence of flooding brought on by climate change presents a growing public health challenge.4 The disease has emerged as a public health priority in Vanuatu, an archipelago nation in the South Pacific Ocean, because of its staggering toll on lives and livelihoods.

Flooding after heavy rains. Credit: praditkhorn somboonsa/Shutterstock

Flooding after heavy rains. Credit: praditkhorn somboonsa/Shutterstock

What Happened

Between March 1 and 3, 2023, two severe tropical cyclones, Cyclone Judy and Cyclone Kevin, made landfall in Vanuatu. The cyclones devastated homes and critical infrastructure, including roads and airports. For several days, more than 80% of the population was left without food, electricity and basic hygiene facilities.5 Cyclone Kevin was particularly damaging to the country’s health system. It made landfall in Efate Island, the island on which the capital city of Port Vila is located. The country’s largest hospital and laboratory and Ministry of Health (MOH) office are all located in Port Vila.

The response teams had fewer resources to deal with the many public health threats the cyclones helped create because of the cyclones themselves.

Philippe Guyant, World Health Organization

Destruction in Vanuatu following the twin cyclones. Credit: ausnewsde/Shutterstock

“The twin cyclones damaged many health facilities across the capital and across the country. Damage to roofing led to broken medical equipment and soiled stockpiles of essential medicines,” said Dr. Philippe Guyant, a medical officer at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Vanuatu. “The response teams had fewer resources to deal with the many public health threats the cyclones helped create because of the cyclones themselves.”

Leptospirosis is endemic in the country, and increased cases are expected in the rainy season. But the extensive flooding caused by Judy and Kevin brought the bacteria out from the soil and into the water, creating ideal conditions for the spread of the disease and other water-borne illnesses.

The Response

In recent years, the MOH has been making strides to anticipate leptospirosis outbreaks during the rainy season in order to minimize the public health impacts and economic burden posed by the disease. This includes ramping up the capacity of the nation’s laboratory facilities, training frontline workers to spot symptoms and arming them with essential medications to treat suspected cases and engaging with local communities to make sure they understand how to keep themselves and each other safe. When the twin cyclones hit, the MOH was able to mount a response building on these ongoing preparedness efforts.

Vanuatu has an early warning and response system for extreme weather events that initiates public health response efforts before the extreme weather event has occurred. When a cyclone is expected, the National Disaster Management Office issues a warning and activates emergency operations centers across the country. This includes the surveillance unit in the MOH, which is responsible for the management of leptospirosis outbreaks as part of the country’s National Health Emergency Operations Center (NHEOC).

Infrared imagery of Judy and Kevin passing through Vanuatu. Credit: NASA and Japan Meteorological Agency’s Himawari-8/AHI

Infrared imagery of Judy and Kevin passing through Vanuatu. Credit: NASA and Japan Meteorological Agency’s Himawari-8/AHI

Once warnings were issued for Judy and Kevin, the surveillance unit held daily meetings with frontline workers across the country to ensure they were trained to spot the symptoms of leptospirosis and other water-borne diseases and that they were equipped with medications to treat any suspected cases. Later, when the cyclones made landfall, medical teams were deployed to the hardest-hit areas—because those were also the areas most likely to experience public health threats like leptospirosis in the aftermath. Frontline workers based in those areas were given priority on rapid diagnostic tests and medications and trained to alert the MOH on any cases and follow up with any patients in need of attention.

In anticipation of the cyclones, the MOH made efforts to make sure they had as many frontline workers on the ground as possible. In addition to deploying all its available medical staff, Vanuatu also engaged its retired nurses to make up for ongoing staff shortages. International health providers, meanwhile, flew in additional frontline workers to support the response. From March 6 to 16, when the country was placed on “red alert” for leptospirosis, those workers identified 10 cases. And within four weeks of the cyclones making landfall, they had alerted the surveillance unit to 19 cases and three deaths, most of which came from Vila Central Hospital in the nation’s capital.

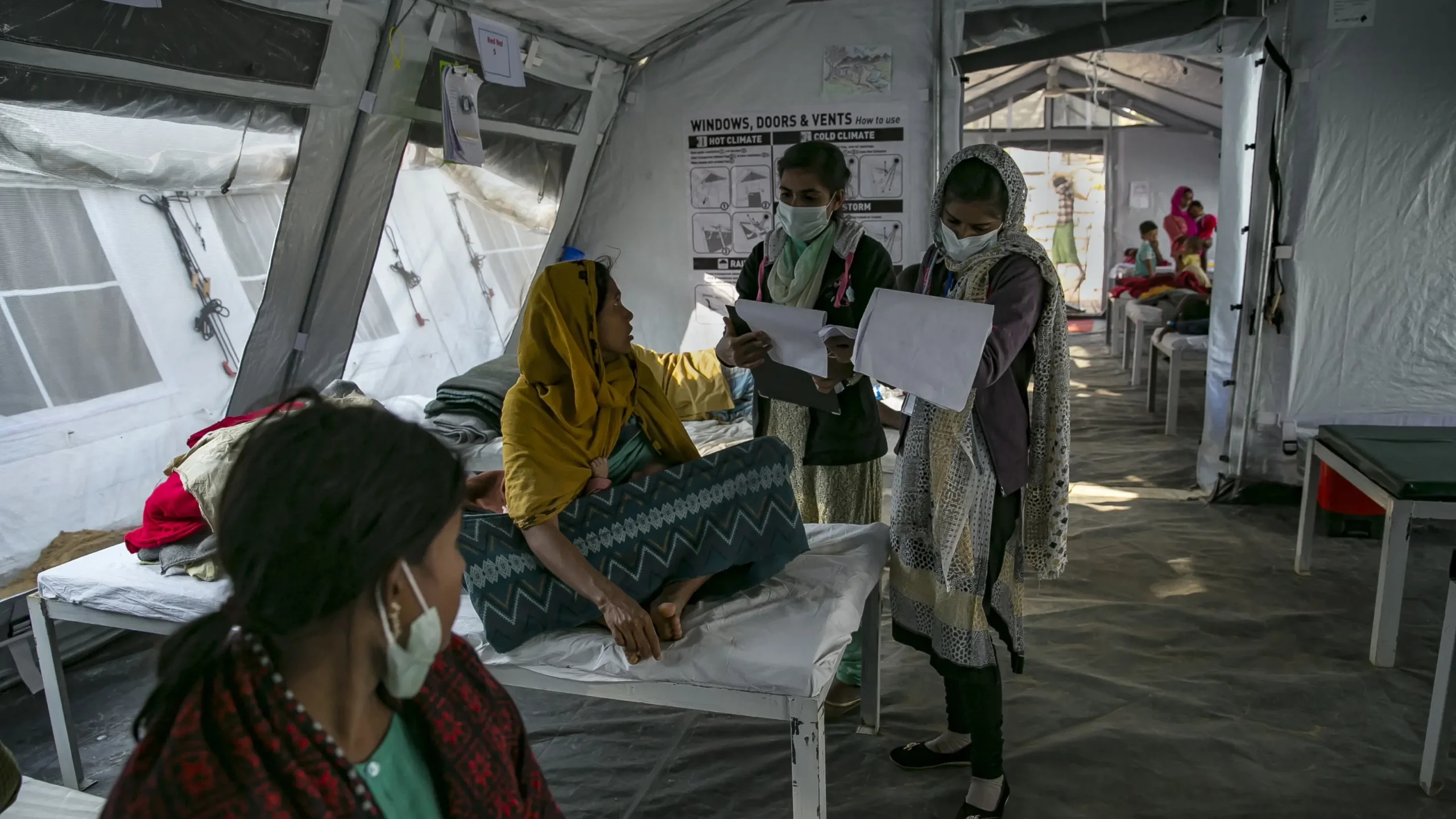

Launching of Vanuatu Leptospirosis Strategy in Sanma province. Facebook.com/WHOVanuatu: World Health Organization; 2021.

The NHEOC, led by the MOH and co-led by WHO, deployed mobile clinics around Port Vila, where around 20% of the population lives.6 These teams went into the affected communities delivering information on how to stay safe from leptospirosis and other water-borne diseases, including by avoiding contaminated water and wearing waterproof boots when outdoors. The teams also encouraged people to seek early diagnosis and treatment if they experienced any symptoms. Leptospirosis outreach and awareness activities were completed in six priority areas across Efate island, where Cyclone Kevin caused significant damage, ultimately reaching 7,875 people.

The Vanuatu Red Cross supported the cyclone response efforts with much-needed equipment to protect local people from water- and vector-borne diseases and other common health issues. They distributed shelter toolkits, tarpaulins, mosquito nets, hygiene kits and dignity kits, which include female hygiene products. The Red Cross also provided jerry cans for storing safe water to help people avoid contaminated water.

Vanuatu is an archipelago with about 80 islands. Transportation between islands requires a plane or small boat and can be limited and cost prohibitive. To reach people in remote areas, health officials posted messages on the MOH Health Promotion Unit’s Facebook page to provide information about leptospirosis and other water-borne diseases. The messages included reminders to boil water and stay out of rivers after flooding. The page has 20,000 followers, about 6% of the country’s population, and was used to disseminate health situation reports. Those followers helped to share this information with the wider community.

To reach people in remote areas, health officials posted messages on the MOH Health Promotion Unit’s Facebook page to provide information about leptospirosis and other water-borne diseases.

Post shared on social media to educate communities on minimizing their risk of infection. Courtesy of Ministry of Health Vanuatu

Post shared on social media to educate communities on minimizing their risk of infection. Courtesy of Ministry of Health Vanuatu

“Moving forward, our new One Health committee will support an even stronger response in future outbreaks,” said Joanne Mariasua, one of the One Health committee leaders at MOH. One Health seeks to recognize the interplay of human, animal and environmental health through effective collaborations across relevant departments that can produce a more effective response and better health outcomes.7 Mariasua says the committee provides clear accountability and will ensure important stakeholders are involved in shaping responses through unique but synergistic lenses. The animal health team, she says, already identified pig enclosures close to homes as a risk factor for leptospirosis, so the committee can now issue advice encouraging residents to move those enclosures further from their homes.

19 cases and three deaths were reported in the first four weeks after the cyclones. By May 26, this had risen to a total of 53 cases and 6 deaths, before cases slowed to a baseline rate typical for the time of year. In contrast, Vanuatu reported 99 cases in 2021 and 59 cases in 2022, illustrating how the MOH’s ongoing efforts to develop critical capacities and mount an effective response prevented a crisis from spiraling into disaster—even against a backdrop of two severe tropical cyclones making landfall.

While the disease is likely to remain endemic for the foreseeable future, WHO, MOH and other Ministries continue to partner with frontline workers and wider communities through a One Health approach to build on these outbreak response efforts, to make sure the nation is prepared to respond to future heavy rains—and any health threats that follow.

Enablers

Climate-responsive operations

Rapid detection, notification and early response actions

Effective multisectoral response

Risk communication and community engagement

Timeline

Emergence

Detection Notification Response

Control

References

- Said, M.S. et al. (2023). Animal Zoonotic Related Diseases. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570559/.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2017). Factsheet about leptospirosis. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/leptospirosis/factsheet.

- Pan American Health Organization. Leptospirosis. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/leptospirosis.

- Lau, C.L. et al. (2010). Climate change, flooding, urbanisation and leptospirosis: fuelling the fire? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 104 (10) 631-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.07.002.

- Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office. (2023). Situation Update 01: TC Judy & Kevin (Tropical Cyclone Judy & Kevin Response NEOC, Port Vila Vanuatu- 2nd- 7th March 2023. https://ndmo.gov.vu/tc-judy-tc-kevin/infographics.

- UN-Habitat. Port Vila Population and Demographics. https://urbanresiliencehub.org/city-population/port-vila/.

- CDC. (2023). One Health Basics. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/index.html.