Epidemics that didn't happen

Neethling Disease in Cambodia

Against a backdrop of an ongoing epidemic in livestock, forest rangers prevented cases spreading to endangered wildlife.

About Neethling

Neethling disease, caused by the Neethling virus, is a highly infectious animal disease that can affect domestic and wild cattle and water buffalo. Neethling is a “transboundary” disease that can spread rapidly across borders and is notifiable to the World Organization of Animal Health.1 It represents an unprecedented threat to cattle and buffalo and outbreaks can have significant impacts on farm economies, international trade, and food security.

Virus Image: A computer-generated image of the Neethling virus. Credit: Uma Shankar sharma via Getty Images

Header: Livestock farmers with buffalo. Credit: Sutipond Somnam/Shutterstock

Biting fly Stomoxys calcitrans, a vector of the Neethling virus. Credit: Trachemys (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Neethling virus is transmitted primarily through arthropod vectors, including mosquitoes and biting flies,1 making it difficult to contain without vaccination campaigns, particularly in places where domestic and wild animals overlap. Infected animals experience fever, anorexia and emaciation, enlarged lymph nodes and characteristic lumps which give the disease its common name—“lumpy skin disease”. These nodules affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue and muscle and can remain infectious for over a month, allowing infections to spread rapidly through herds of animals—a big problem for livestock farming.

This once obscure disease is now spreading at alarming rates and is endemic in most African regions.

Cow displaying symptoms of Neethling disease. Credit: Pornsawan Baipakdee/Shutterstock

Cow displaying symptoms of Neethling disease. Credit: Pornsawan Baipakdee/Shutterstock

Neethling ultimately results in significant economic losses for farmers due to reduced milk production and weight loss, miscarriage and infertility, damaged hides and death of severely infected animals. This once obscure disease is now endemic in most African regions. It’s also causing epidemics in major cattle-producing regions across Asia. Regional and global action is needed for effective disease prevention and control efforts to mitigate ongoing economic losses at national and international levels.

What Happened

In late 2020 and early 2021, several epidemics of Neethling were observed in China, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. The disease was first detected in domestic cattle in Cambodia in June of 2021, creating concern for the health of domestic and wild populations. By September 2021, Neethling had spread to all provinces throughout Cambodia and infected over 73,000 domestic cattle.2 Because farmers in Cambodia do not typically fence in their cattle, which are free to roam and graze across wildlife sanctuaries, the outbreak presented an enormous threat to wild cattle species like the endangered banteng and vulnerable gaur, which each have critical roles in local ecosystems including seed dispersal and nutrient cycling, as well as major cultural significance in local folklore and traditions.

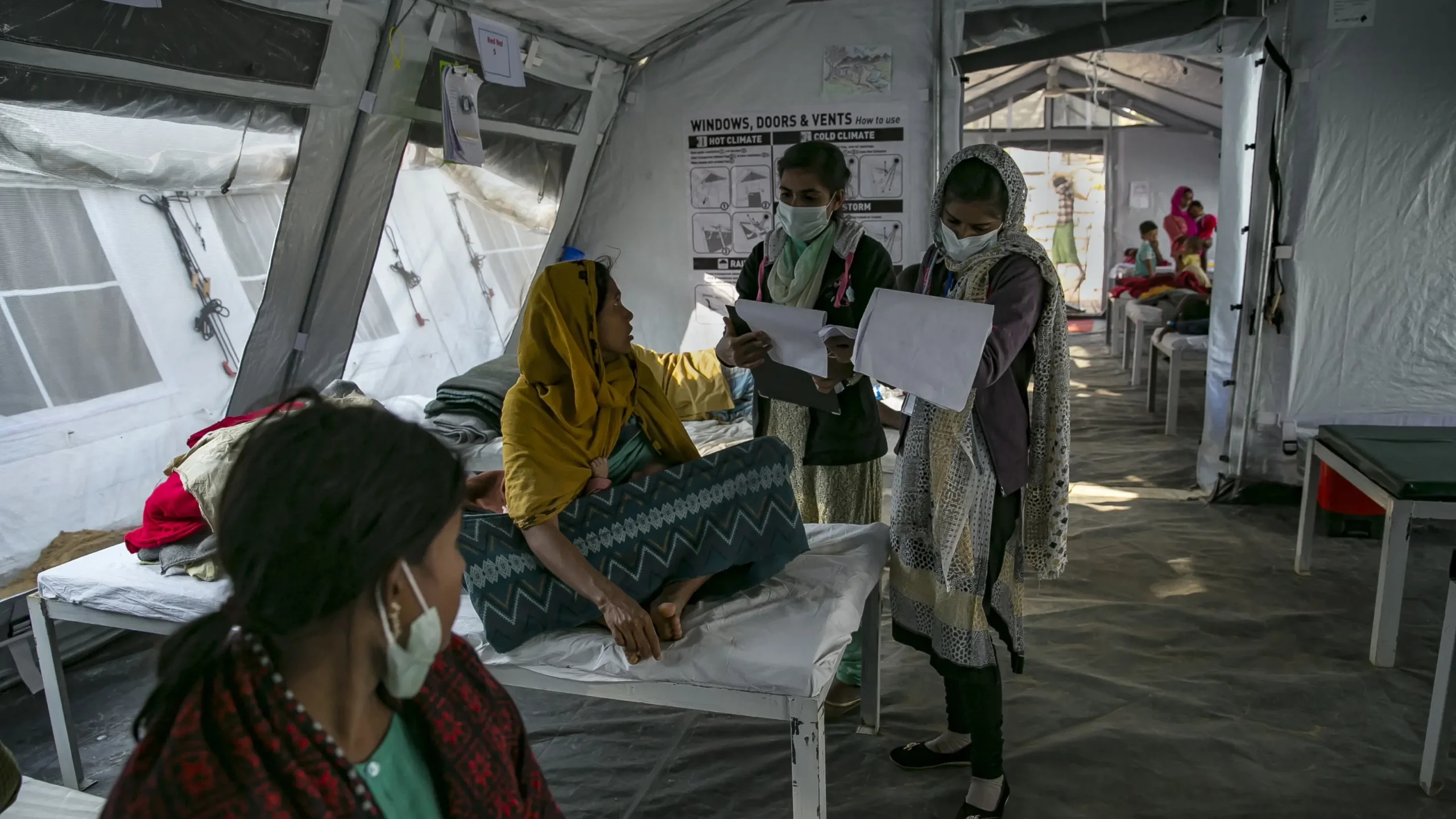

A Cambodian village. Credit: imagesef/Shutterstock

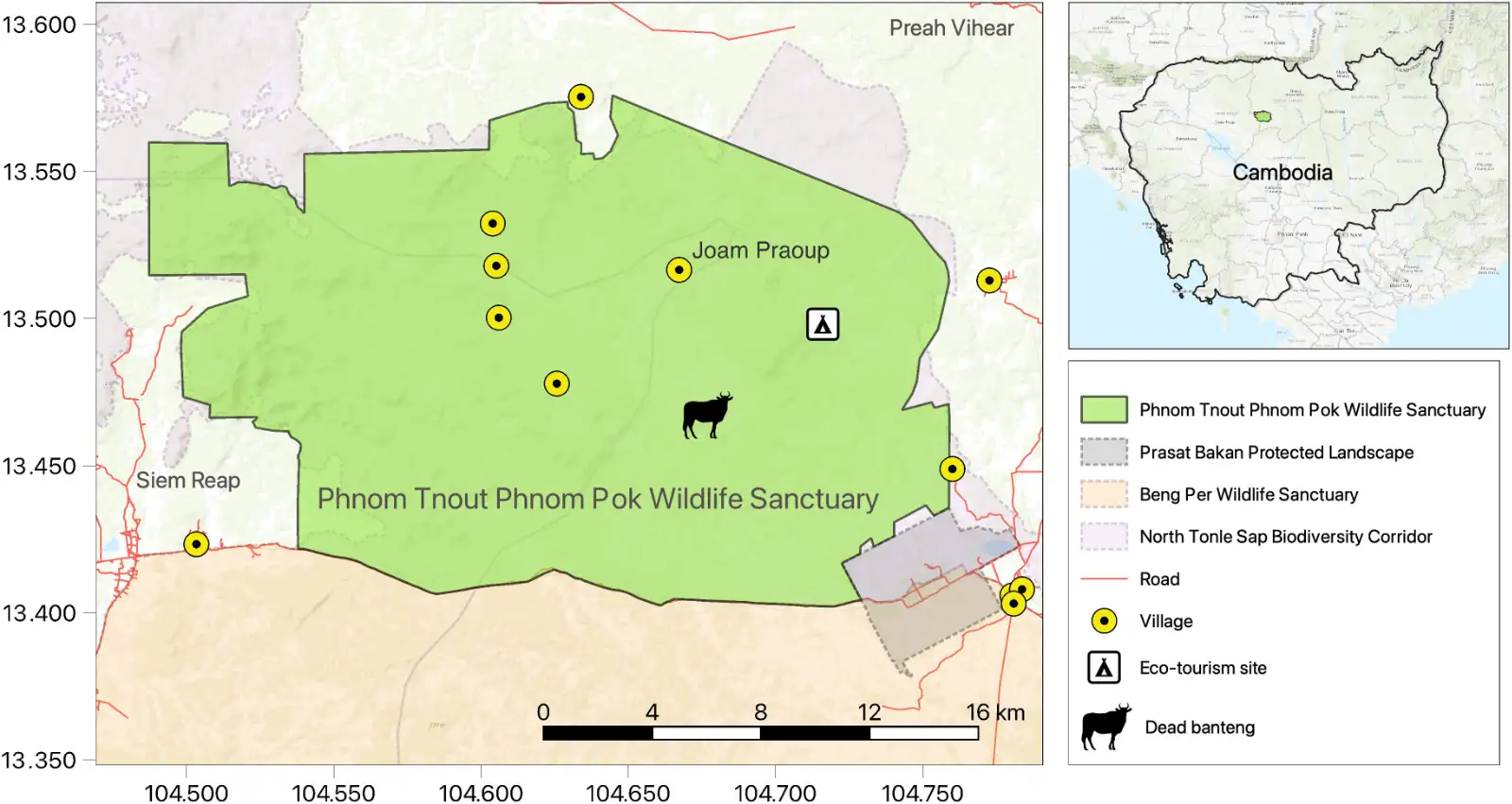

Since 2019, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) has worked with governments in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, to build and operate wildlife health surveillance systems, supporting timely infectious disease response and broader One Health efforts to protect the health of humans, animals and their shared environments. On September 8, 2021, community rangers in Phnom Tnout Phnom Pok, a wildlife sanctuary in northern Cambodia, spotted a wild banteng with characteristic signs of Neethling. The banteng had skin nodules on its head and flank, was thin and lethargic and eventually died two days later. A veterinarian was requested and sent to the site to collect blood and scab samples from the lesions, and the animal was incinerated at the site as a precautionary measure. Laboratory tests later confirmed that the banteng was positive for the virus.2

A banteng bull. Credit: RudiErnst/Shutterstock

The Response

The infected banteng was the nation’s first recorded case of Neethling in wild cattle. Because Cambodia was dealing with an epidemic of Neethling in domestic cattle, and neighboring Thailand had already detected the disease in wild cattle, community rangers were on high alert to spot any signs of the disease in wild cattle while managing the forests. Through their ongoing collaboration with WCS, the rangers were trained to quickly notify WCS’s Wildlife Health Surveillance Network—known as WildHealthNet—as soon as they spotted a potential case.

Local communities and local community rangers are the eyes and ears of the forest. Without them, we would have never identified this case.

Cain Agger, Wildlife Conservation Society

Camera trap image of Phnom Tnout Phnom Pok Wildlife Sanctuary. Courtesy of Cain Agger

Camera trap image of Phnom Tnout Phnom Pok Wildlife Sanctuary. Courtesy of Cain Agger

“Local communities and local community rangers are the eyes and ears of the forest,” said Cain Agger, Biodiversity Monitoring Technical Advisor for WCS in Cambodia. “Without them, we would have never identified this case, putting the entire nation’s populations of wild banteng and gaur at risk. It’s thanks to ongoing relationships with this community that the case was brought to our attention so we could respond and keep wildlife safe.”

After the case was detected, WCS and its partners at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) met with the Cambodian General Directorate of Animal Health and Production (GDAHP) to develop a strategy for protecting domestic livestock and wild species. Because there are so many spaces where domestic and wild cattle coexist, there are many opportunities for transmission of pathogens from domestic to wild animals. Typically, such a response effort would involve restricting the movement of animals to stop the spread of disease, but this is not possible when trying to protect free-roaming wild populations. Instead, the vulnerable “domestic-wild cattle interface” became the focus of the team’s major outbreak response effort—a massive vaccination campaign of domestic cattle to protect vulnerable wild species.

But when the outbreak began, GDAHP had just 27,000 vaccine doses available to protect over 1.3 million susceptible wild cattle across the country.2 This was a challenging constraint, but WCS and its partners agreed to conduct a targeted vaccination campaign of domestic cattle and water buffalo for a 20-kilometer radius around three wildlife sanctuaries in Cambodia’s Eastern Plains, and four sanctuaries in the Northern Plains. These strategic locations were selected based on their importance to wild banteng populations and the range of a suspected insect vector. The team distributed the vaccine doses, along with needles and syringes, to the seven wildlife sanctuaries.2

Map of Phnom Tnout Phnom Pok Wildlife Sanctuary showing the location of the infected banteng. Courtesy of Wildlife Conservation Society

At the start of the vaccination effort, the team held outreach meetings to explain the condition, that it was spreading in local cattle, and to advocate that farmers bring their cattle back from roaming the sanctuaries to be vaccinated by village animal health workers. According to Agger: “Each village has a vet who is trained to administer vaccines. These trusted community members also help local farmers understand how vaccinating their livestock will help keep them safe from the disease for another year.”

Where WildHealthNet’s monitoring activities rely on established relationships with trained rangers, its response efforts rely on local veterinarians and their deep connections with farmers and village communities. Agger says these collaborations are vital to the success of this work. The collaboration across sectors for Neethling demonstrates the trust built over time amongst key multisectoral stakeholders relevant to infectious disease detection and response at the human-animal-environment interface. This collaboration also creates a foundation of partnership and joint surveillance that has the potential to increase preparedness for other health security challenges.

A veterinarian prepares a vaccine as part of the immunization campaign. Courtesy of Cain Agger

Each village has a vet trained to administer vaccines. They also help local farmers understand how vaccinating their livestock will help keep them safe from the disease.

Cain Agger, Wildlife Conservation Society

A veterinarian prepares a vaccine as part of the immunization campaign. Courtesy of Cain Agger

A veterinarian prepares a vaccine as part of the immunization campaign. Courtesy of Cain Agger

The Eastern Plains vaccination campaign ran from July 21 to December 28, 2022, and the Northern Plains campaign from August 20 to October 12, 2022. Through these initial campaigns, 14,226 domestic cattle and 2,646 water buffalo were vaccinated in the Eastern Plains and 2,676 domestic cattle and 541 water buffalo in the Northern Plains. The remaining 2,000 doses were later distributed through both locations as part of a follow-up vaccination effort in May 2023, when the Cambodian government also committed to continuing its vaccination efforts for an additional three years.

Immunization campaign materials in a Cambodian village. Courtesy of Cain Agger

WildHealthNet, meanwhile, continues to monitor Cambodia’s wildlife sanctuaries through its network of forest rangers, conservation workers and camera traps, building a trusted multisectoral, One Health network that can continue working on health security challenges. Since the first case in the wild banteng was discovered, no additional cases have been identified in wild banteng or gaur.

Enablers

Cross-border communication

Rapid detection and notification

Park rangers contributing to public health

Veterinarians with local knowledge and relationships

Timeline

Emergence

Detection

Notification

Response

Control

A veterinarian vaccinates livestock. Courtesy of Cain Agger

References

- World Organisation for Animal Health. (2022). Lumpy Skin Disease. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2022/06/lumpy-skin-disease-final-v1-1forpublication.pdf

- Porco, A. et al. (2023) Case report: Lumpy skin disease in an endangered wild banteng (Bos javanicus) and initiation of a vaccination campaign in domestic livestock in Cambodia. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1228505