Epidemics That Didn't Happen

Case Study:

Anthrax

in Kenya

ABOUT ANTHRAX

Although anthrax is commonly associated with bioterrorism, it is an ancient disease that some scholars believe is referenced in the writings of Homer and Virgil and even the Biblical plagues of Moses,1 as well as in ancient China.2 Anthrax is a bacterium found naturally in soil that can infect livestock and wildlife as they graze.3

Humans can become infected by eating infected meat, or through a cut in the skin that becomes exposed to bacteria when slaughtering or handling animals; human-to-human transmission is uncommon.

Initial symptoms can be similar to the flu, but later stages include poor liver and kidney function and internal and external bleeding.3 Supportive treatment, such as oral or intravenous fluids, dramatically improves chances of survival, and a treatment was approved in 2020.4 Effective vaccines have been available since 2019, but supply remains limited, and there are significant logistical challenges for delivery.5

Key Preparedness Factors

-

Risk Assessment & Planning

-

Emergency Response Operations

-

National Laboratory System

-

Disease Surveillance

-

National Legislation Policy & Financing

-

Human Resources

-

Risk Communications

WHAT HAPPENED

On August 15, 2019, in Narok—a town in the southwestern part of Kenya along the Great Rift Valley near the Maasai Mara National Reserve—a Red Cross volunteer received some disturbing news.

A community member shared that a local young herder and two students had eaten meat from a dead cow and were now sick. When they arrived at the nearest health facility, all three were diagnosed with anthrax.

THE RESPONSE

The volunteer, who had recently received training from the Kenya Red Cross Society’s Community-Based Surveillance system, took immediate action, sending an SMS alert to the system. The alert was received by a supervisor who notified the local health and veterinary authorities, triggering action through the government’s national surveillance system.

Through Community-Based Surveillance, our community members are now aware of basic signs of potential epidemic diseases like anthrax, and they can report to us instantly so that we can upscale the case to our supervisors. Our community members are also shunning away unhealthy habits like handling dead animals since we have been creating awareness through many platforms, for example community dialogues and household visits.

Red Cross CBS Volunteer

The key to preventing anthrax in humans is controlling infection in livestock.

Community-based surveillance, which allows disease surveillance to happen in communities by community members, is a component of the Community Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness Program led by the Kenya Red Cross Society, with support from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The program recognizes that information about the beginning of outbreaks often reaches standard surveillance systems late. It works to connect communities with the national health and surveillance systems, training members to participate in notification of high-risk diseases. It is simple, adaptable and low-cost.

The volunteer reported that, even though the local Maasai, a semi-nomadic herding community, was familiar with anthrax, many were skeptical of its risks. Goats and sheep in the affected area were also showing signs of illness.

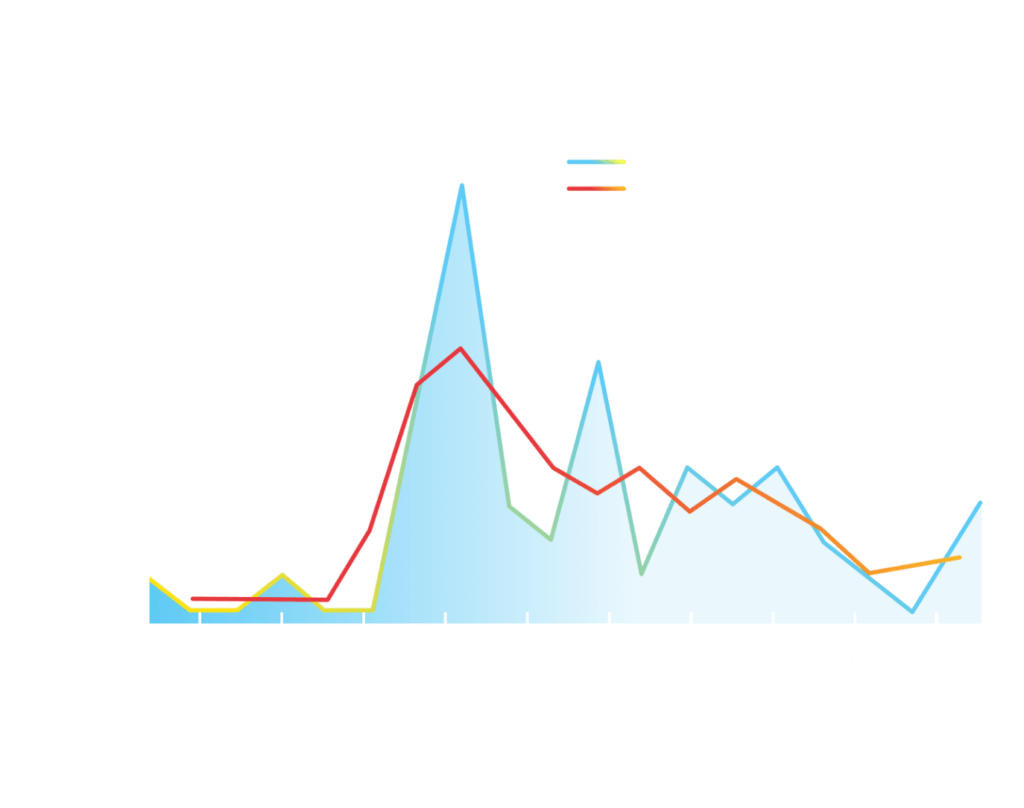

The Community-Based Surveillance message led the supervisor and Government County Veterinary Officer to investigate the health of livestock in the area. Within days, the county vaccinated 10,600 cattle and 14,000 sheep in the vicinity.

By just over a month after the incident, the situation was under control after four human cases and one death, and the community was safer and better prepared than it had been before.

To gain the trust and participation of local farmers, the government and Red Cross immediately convened a traditional community dialogue session. School teachers were shown how to screen potentially infected children and report any incidence of illnesses to public health officers or area volunteers. The Community Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness Program also conducted wider health information and awareness-raising activities, such as radio broadcasts, school activities, household visits and community group education sessions. These activities improved community health knowledge and practices on safe disposal of animal carcasses, reporting unusual animal illnesses and general information on disease outbreaks. The outreach work was so successful that the community recognized the risk, prioritized mitigation efforts and has taken over financing its own animal vaccinations.

By just over a month after the incident, the situation was under control after four human cases and one death, and the community was safer and better prepared than it had been before.

This case study was developed in partnership with the Kenya Red Cross and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

TIMELINE

We thank the Kenya Red Cross Society for initiating the community-based surveillance concept that has strengthened weak linkages of facility-based surveillance by capacity building. Community health volunteers do real-time reporting of potential epidemic diseases from the community.

County Government Disease Surveillance Official (Health sector)

This facilitates quick and timely response to save lives.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, November 20). History of Anthrax. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/basics/anthrax-history.html

- Li, Y., Yin, W., Hugh-Jones, M., Wang, L., Mu, D., Ren, X., Zeng, L., Chen, Q., Li, W., Wei, J., Lai, S., Zhou, H. & Yu, H. (2017). Epidemiology of Human Anthrax in China, 1955−2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(1), 14–21. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/Anthrax/en/

- World Health Organization. (2018, April 16). Anthrax. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/Anthrax/en/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). (2020a, November 20). Anthrax | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, November 20). Anthrax | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/index.html

- Li, Y., Yin, W., Hugh-Jones, M., Wang, L., Mu, D., Ren, X., Zeng, L., Chen, Q., Li, W., Wei, J., Lai, S., Zhou, H. & Yu, H. (2017). Epidemiology of Human Anthrax in China, 1955−2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(1), 14–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5176222/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, November 20). History of Anthrax. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/basics/anthrax-history.html

- World Health Organization. (2018, April 16). Anthrax. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/Anthrax/en/